This project unfolds across multiple stages and layers over time.

The following article is written by Yipei Lee

Place and Memory

In my childhood, the presence of camphor trees was always accompanied by their scent. They were my grandmother’s companions, and the fragrance that drifted from the small white balls in her wardrobe. The smell was slightly pungent, yet not as sharp as mint; over time, it exuded a subtle sweetness. Each time I inhaled it, it felt like being gently embraced by a quiet, stabilizing force.

In the city, camphor trees form lines of street trees. Along Dunhua South and North Roads, rows of greenery shift with the seasons; in the 1932 Taipei urban plan, Ren’ai Road was designed as a park avenue, lined with camphor trees. During the Japanese colonial period, Zhongshan North Road, as a path leading to the Shinto shrine, was also accompanied by camphor trees. They are not only the green veins of the city but also witnesses of history.

In the collective memory of many Taiwanese, camphor trees were once part of a thriving 19th-century industry. With the invention of smokeless gunpowder, celluloid, and photographic film, the demand for camphor surged. At one point, Taiwan’s camphor production accounted for 70% of the world’s total, earning the island the title of “Camphor Kingdom” for half a century. This chapter of history gradually closed with the emergence of chemically synthesized camphor.

In the early days, many ancient trails were carved through the mountains to transport camphor and tea, carrying the footsteps of generations. Today, camphor trees remain present in our lives in various forms: ancient trees in sugar factory parks, courtyards of Japanese-style dormitory clusters, the shade beside school basketball courts, street trees guarding the front doors of homes, and even the familiar scent inside our wardrobes. Camphor trees have long been deeply embedded in our daily memories and the textures of life; they are part of Taiwan’s everyday landscape and the lingering fragrance of our collective memory.

[2016]

First Attempt to Barus; Family Treasure (remastered) by Aliansyah Caniago (Duration: 04:00)

Courtesy of Artist

[2018]

Chapter I : Taipei Botanical Garden

Camphor Tree from the Botanical Garden. It’s a historic tree recorded as early as the Japanese colonial era.

Courtesy of Yipei Lee

Performance and onsite installation by artist Aliansyah Caniago in 2018.

Click here for reading more process and story during the residency program.

Courtesy of Yipei Lee

Aromatic and medicinal plants have long been used by humans as spices and remedies. Many of today’s commonly used essential oils still originate from these plants. Take camphor, for example: derived from trees of the genus Cinnamomum, it has a wide range of applications—from medicine and spices to industrial products.

The genus Cinnamomum itself is a large family, comprising around 250 evergreen species, belonging to the Lauraceae family. This plant family holds both economic value and key ecological roles. Globally, approximately 2,850 species are known, primarily distributed across tropical and subtropical regions of Asia and South America. Many familiar plants come from this family: the avocado (Persea americana) on our tables, the bay leaf (Laurus nobilis) used in cooking, camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora) for camphor extraction, and cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia and related species) that gives off a rich fragrance.

In botanical terms, Lauraceae falls under the Magnoliids’ order, related to families such as Piperaceae, Canellales, and Magnoliaceae, forming cross-species kinships spanning spices and ornamental plants.

Camphor Trees as Living Archives

Camphor (Cinnamomum camphora) is a white crystalline substance with a strong aroma and pungent taste, derived from the wood of camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora) and related Lauraceae species. Camphor trees are native to China, India, Mongolia, Japan, and Taiwan, and their aromatic evergreen varieties have also been introduced to the southern U.S. states, especially Florida. Camphor is typically obtained through steam distillation, purification, and sublimation of the tree’s wood, branches, and bark.

Historically, camphor trade was highly active. Marco Polo noted that camphor had been exported from Southeast Asia to the Middle East since the 6th century (Polo 1845). Furness (1902) and Nicholl (1979) reported on camphor trade among local communities in China and Borneo. Lundqvist (1949) mentioned the Dayak people trading camphor at Nunokan in Borneo, possibly with Arab merchants. Even in the 1950s, Bornean camphor remained a rare and highly valuable commodity (Césard 2007). Engaging with literature has expanded our knowledge. Situated in the natural habitat of camphor trees, the species itself becomes a “witness of inter-island distribution”—growing both on the continent and proliferating across tropical islands.

Proses Penyulingan Pohon Kamper

Distillation Process of the Camphor Tree by Aliansyah Caniago

07:51 / 2019

Courtesy of Artist

This video documents the methodology of camphor distillation in Miaoli. Essentially, the Japanese adopted Western chemical distillation concepts but developed in Taiwan a large-scale, systematized method for extracting camphor and camphor oil.

Video works by Aliansyah Caniago

Tree without Roots; Barus Tree / 31:14 / 2019

–

Performance at Taipei Botanical Garden

4 days performance, 9 hours each day. 2018

Courtesy of Artist

[2019-]

SUAVEART Archive

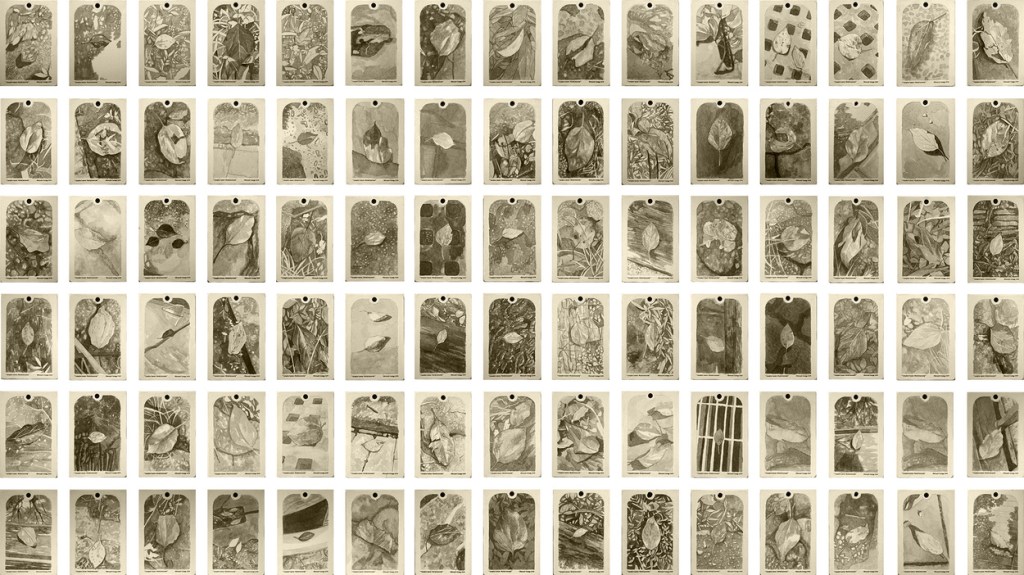

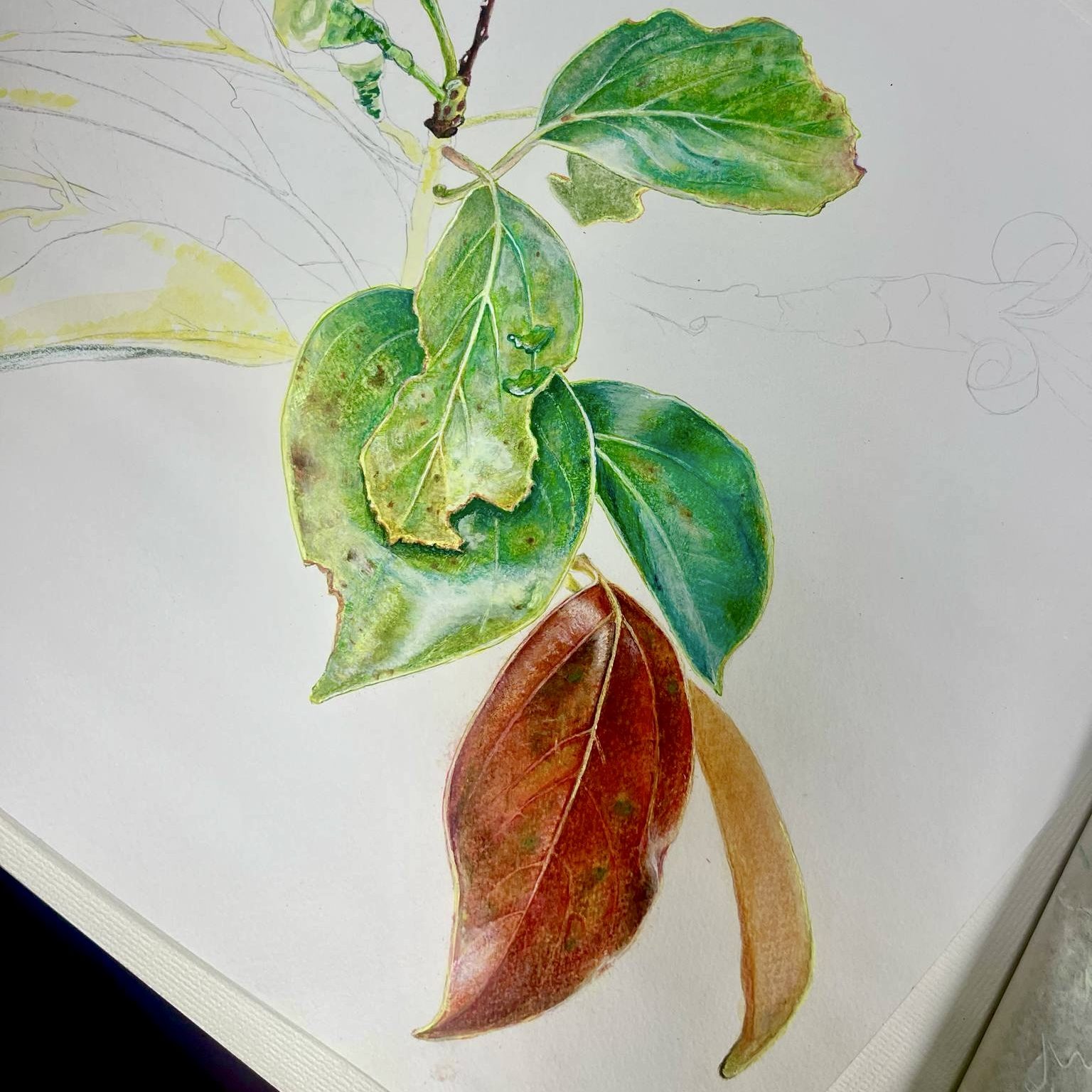

Click here for viewing more photographs of Camphor tree leaves.

Courtesy of contributors: Jo-ku Chen, Bo-Yu Yao, Lois Chen, Ming-Yuan Chen, Lin San-Yuan, Kun Da Li, Ling Huang, Yipei Lee, Chou Li Hong, Chen Chun Yin, Kung Li Chin

[2019]

Chapter II : Moving to Jakarta

Mortal Immortal: Leaves from The Same Tree by Aliansyah Caniago. The project exhibited at Indonesian Contemporary Art and Design X, Curated by Hafiz Rancajale

Courtesy of Artist

From Place to Elsewhere

Ecologically, Taiwan and Southeast Asia have long shared subtle yet rich interactions. In the early years of SUAVEART Studio, based next to the Taipei Botanical Garden, we observed plants along streets, gardens, and commutes. Combined with visits to Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, we were able to observe to varying degrees, the growth and distribution of camphor trees:

In central Vietnam and the highlands, camphor trees are common, with wood and camphor oil traditionally used. Southern Vietnamese border areas were also among the ancient routes of camphor trade. In the forests of the Philippine islands, native species such as Cinnamomum mercadoi (named after the Filipino botanist Mercado) are used locally for medicine and spices.

Spice-bearing camphor trees were part of the early Malacca Sultanate trade network. In the tropical rainforests of Malaysia and Singapore, wild cinnamon (Cinnamomum species) forms part of the traditional spice heritage, and Singapore Botanic Gardens preserves multiple Lauraceae species.

Camphor trees are found throughout northern, central, and southern Thailand, where their leaves are used medicinally and wood for temple architecture and carvings. In Thai, camphor trees are often called “การบูร” (typically Cinnamomum camphora), while “เทพทาโร” or commonly “การบูรป่า” (Cinnamomum porrectum) are especially found in southern Thailand. Aromatic Lauraceae appear in traditional Thai texts and long-distance trade narratives, used in cuisine, medicine, postpartum care, and rituals, and have been subjects of modern pharmacological research. Thai botanical records describe camphor distribution from the southern slopes of the Kunlun Mountains to the Malay Peninsula. Recent taxonomic updates in Thailand include Cinnamomum thailandicum, indicating that Lauraceae diversity is still being revised.

The Indonesian archipelago is a major center for cinnamon, many species of which belong to the genus Cinnamomum. Sumatra and Java were historically important sources for camphor and spice exports. Cinnamomum sintoc (locally called sintok or medang sintok), native to lowland Java and Sumatra, has bark traditionally used in folk medicine for digestive issues, diarrhea, and topical wounds, while its wood and essential oil are valued for medicinal and aromatic purposes.

The camphor tree reflects what I perceive as a kind of inter-island resonance.

By considering camphor trees as a “cross-island species,” I believe there are many narratives yet to be explored. Its roots are localized, yet its leaves reach across the ocean, creating a sense of “shared breath” among scattered islands. They symbolize invisible networks connecting species, people, and cultures.

Historical Context of Camphor: From the Qing Dynasty to the Japanese Colonial Period

While Taiwan is an isolated island spanning both tropical and subtropical latitudes, its vertical elevation provides a wide variety of forests from tropical to frigid zones, leading to a rich diversity of native tree species. Among them, the camphor tree is a unique product of Taiwan, mainly distributed in the central and northern parts of the island, becoming scarcer further south. In the early Qing dynasty, camphor trees were abundant in the mountains and plains of central and northern Taiwan and were transported via ancient trails. However, starting in the Yongzheng period (1723), the Qing imperial court began cutting down camphor trees to build warships, and private individuals also secretly produced camphor, causing a decline in the camphor tree population.

The true cause of the significant decline in Taiwan’s camphor tree population was the rise of the celluloid nitrate industry in the 19th century. This synthetic material required camphor as a raw material, gradually making it an important international trade commodity. After Japan took control of Taiwan in 1895, camphor was considered a valuable economic asset by the Governor-General’s Office. In September of the same year, Civil Affairs Bureau Chief Mizuno Jun announced in his “General Administration of Taiwan” that to control forest resources, they would implement policies to manage the indigenous population and divide forests into state-owned and private lands, strictly regulating the cutting of camphor trees and the manufacturing of camphor.

The following October, the Taiwan Governor-General’s Office issued three regulations concerning camphor manufacturing. The main stipulations were that:

- Individuals without a manufacturing permit from the Qing government were prohibited from producing camphor, with violators subject to fines of 50 to 500 yen.

- Existing manufacturers had to obtain official approval by a specified date and submit a notarized application form with the required information.

- If no application was submitted, or if the permit was found to be fraudulent, local authorities could seize and confiscate the products and raw materials.

Subsequently, through the “Camphor Tax Regulations” issued on March 5, 1896, and the “Camphor Oil Tax Regulations” issued on August 29, 1897, the Governor-General’s Office incorporated camphor into the main tax revenue streams and made the camphor business a state monopoly.

To gain control of more camphor tree resources, the Governor-General’s Office partnered with the Tokyo Imperial University to conduct a comprehensive forest survey focused on camphor, starting in 1896. The survey covered regions including Hsinchu, Miaoli, Puli, Taichung, Tainan, Yilan, and Taitung. From 1896 to 1899, several technicians, including NISHIDA Mataji, KONISHI Narishige, IKE Eusuke, YAHATA Michio, and TASHIRO Antei, conducted forest surveys. Their findings revealed that due to the booming camphor industry and land clearing by Chinese settlers, camphor manufacturers were only extracting oil from the tree trunks and carelessly discarding the rest, leading to significant resource waste. The technicians recommended not only making better use of the resources but also calculating the timber yield before felling to plan appropriate afforestation methods, plant high-quality trees, and improve soil productivity.

The Promotion and Challenges of Afforestation

In 1899, as the international demand for camphor increased, technician OGASAWARA Tomijiro (小笠原富次郎) stressed the urgency of independently implementing an afforestation plan to maintain production. In the same year, technician TASHIRO Antei surveyed the forests along the Beishi River in the Wenshan District and found that while there were few camphor trees, their quality was superior to those in other areas. He recommended that to properly care for camphor seedlings, it was essential to regularly weed and clear away brush to prevent them from being overshadowed and killed by other plants, and to transplant them to suitable forestland once they had grown into seedlings.

To solidify the camphor monopoly system and maintain fiscal revenue, the Taiwan Governor-General’s Office not only improved old production methods but also implemented the camphor monopoly system in August 1899 and officially launched Taiwan’s first “camphor tree afforestation” project in 1900 to ensure the reserve of camphor resources. Despite facing initial obstacles such as unclear forest conditions, banditry, labor shortages, and endemic diseases, the project successfully met its intended goals. By the end of Showa 12 (1937), the total area of government-run afforestation had reached over 19,700 hectares. Simultaneously, the Governor-General’s Office also encouraged private afforestation, issuing the “Taiwan Camphor Tree Afforestation Encouragement Regulations”, which provided free seedlings and technical guidance. As a result, by the end of Showa 12 (1937), the total area of private camphor tree afforestation had reached 26,660 hectares, accounting for about 13% of the total private afforestation area.

Camphor Varieties and Future Development

In the 1890s, the development of synthetic camphor posed a threat to the natural camphor industry. The Governor-General’s Office began to place importance on the development of synthetic camphor. The camphor tree varieties on the island include Camphor tree (本樟), Aromatic Camphor (芳樟), Stout camphor tree (油樟), and Yin-Yang Camphor (陰陽樟) (a camphor tree variant). Aromatic Camphor is a unique variety to Taiwan and is not found in Japan. It contains Linalool, a fragrant oil that has gained significant value in the chemical industry and now holds a leading global position in the perfume industry. In terms of camphor oil yield, Camphor tree and Stout camphor tree are the best, while Aromatic Camphor is slightly inferior. These varietal differences also influenced the afforestation strategy, prompting the Governor-General’s Office to focus on selecting appropriate varieties and planting locations to meet the evolving market demand.

Reference:

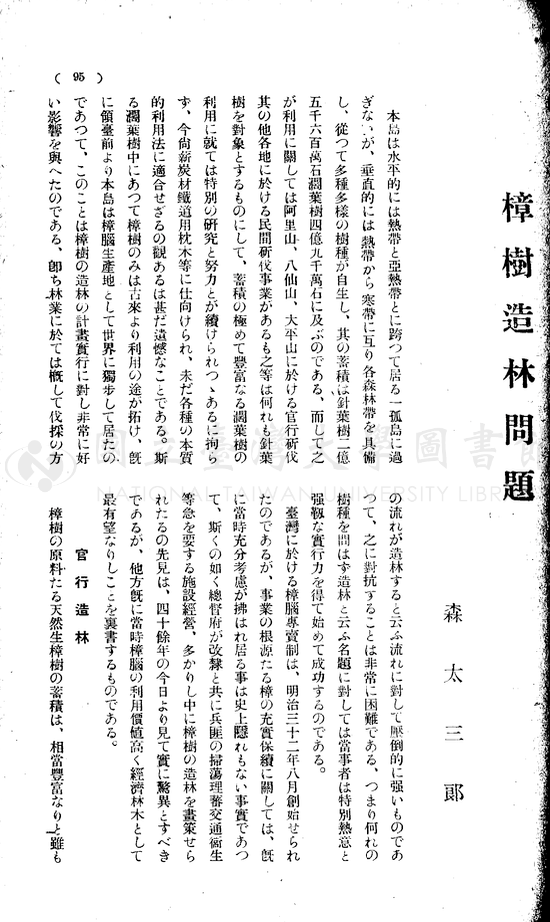

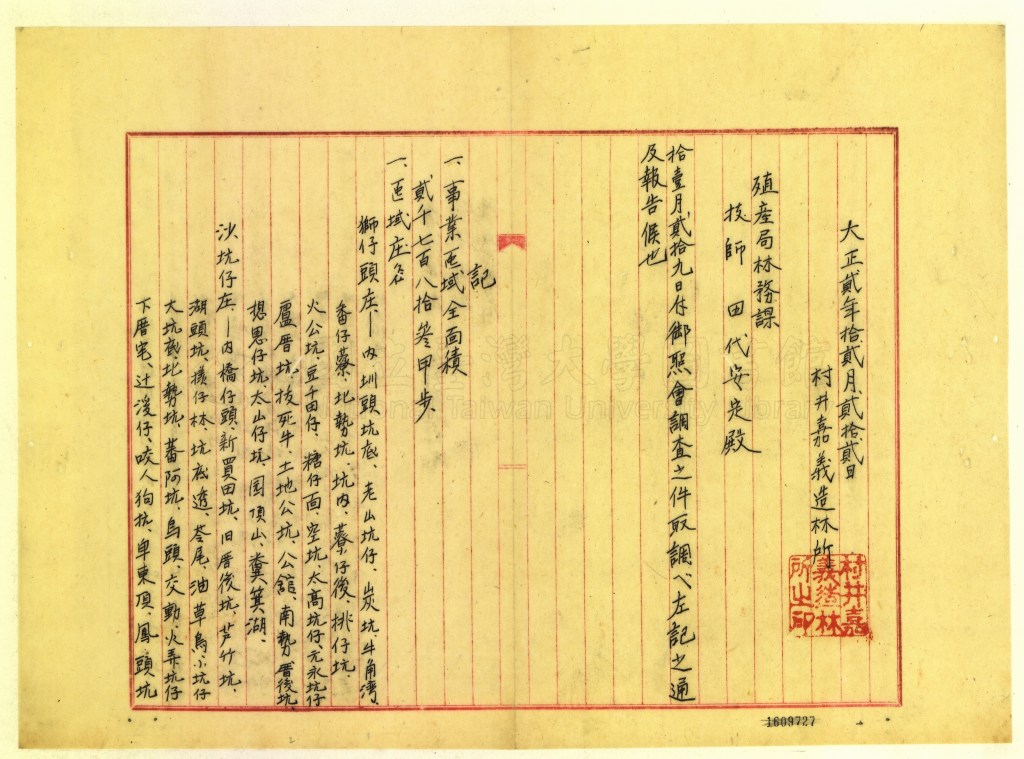

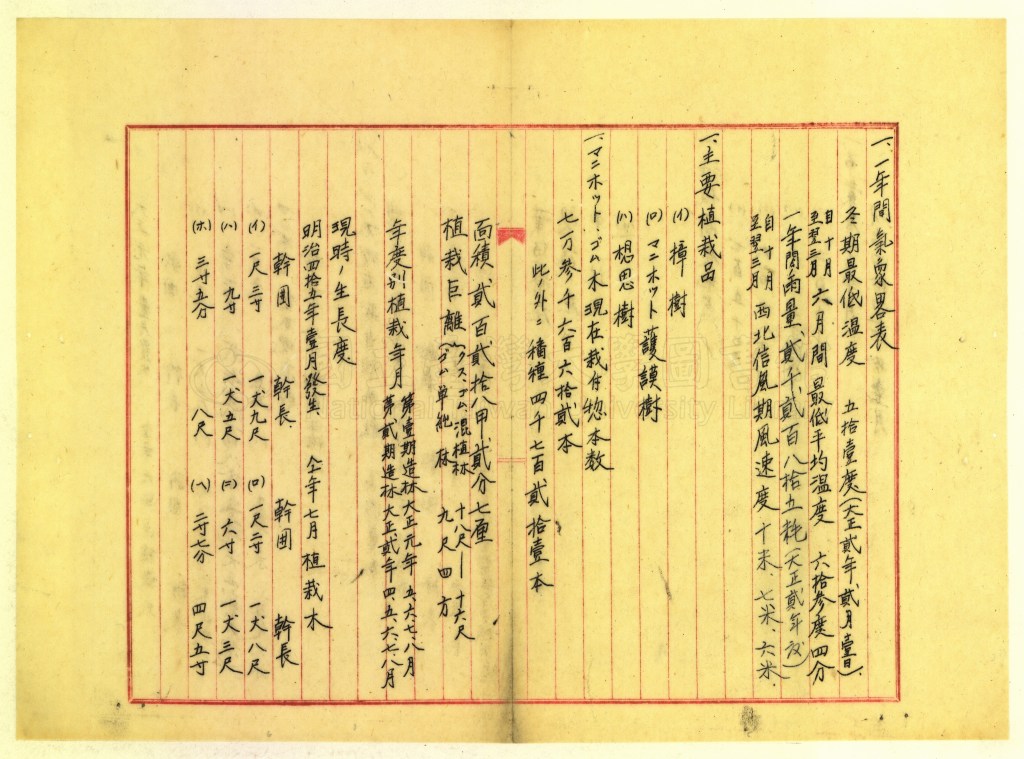

(Left) Article “The Issue of Camphor Tree Afforestation” from 森太三郎.

(Right) Letter from Murai of the Chiayi Afforestation Station to TASHIRO Antei [村井嘉義造林所致田代安定函] / 1913

Resource: Database of TASHIRO Antei in National Taiwan University Library

My Impressions of the Camphor Tree

by Hsin-Chieh Hung

Click Here for more stories

Courtesy of Artist, plant hunter

[2025]

Memory of Camphor Tree

Courtesy of Co-creator: Mr. Cai

[2025]

My Impression of Camphor Tree

Courtesy of Co-creator: Jill Zheng

[2025]

A-Gai’s Camphor Tree

Courtesy of Co-creator: Hsin-Chieh Hung

Cultural Meaning of Camphor Tree

My curiosity about camphor trees has led me to explore their presence across Asia. In the hometown of the Indonesian artist, there is even a city named Barus, once famous for camphor. During my stay in Shanghai, I also noticed how often neighborhoods, communities, and residential buildings are named after the “Camphor Tree”—a name people seem to embrace with affection.

Within Chinese culture, camphor embodies protection, sustainability, and longevity. Its fragrance preserves and repels insects, symbolizing purity and stability. Villages often gather around a large camphor tree, forming a “natural community living room,” a collective spiritual center. In this way, camphor trees came to embody both the physical and spiritual center of collective life.

From a cultural perspective, naming is a way to “domesticate” nature, marking places, streets, and neighborhoods as human territory, preserving memory while shaping imagination. Whether as a place name, neighborhood, or street, naming functions as both a form of possession and a marker of memory. Through naming, a place is inscribed onto the human linguistic map, transforming the wilderness into “our place.” In a sense, this is also a way for humans to “hold nature through language.”

Yet, there is an inherent contradiction behind naming. When indigenous people of Sumatra name locations after trees, the reality is often accompanied by the exploitation and sacrifice of natural resources. Such naming preserves the natural history of a place (its mnemonic function) while allowing later generations to project ideas of protection and elegance (its imaginative function). At the same time, it reveals another tension: nature is celebrated and consumed in language, yet increasingly absent in reality.

[2025]

SWAB Barcelona

POSTER –

lumbung press & Oksasenkatu 11

Courtesy of Yipei Lee

To Be Continued . . .

Acknowledgement:

Our acknowledgements trace back to 2016, when SUAVEART was embraced with generosity and support. Along the way came workshops and conversations, encounters and interactions, stories exchanged, co-creations unfolded, and moments of joy shared—each becoming part of the roots that continue to nourish us today.

Aliansyah Caniago, Hsin-Chieh Hung, Evamaria Schaller, Jill Zheng, Lorena Tabares Salamanca, Lizette Nin / Tangent Proyectos, Patrick Tantra, Donnin Arifianto, Rico “Obos”, Fracis Cai, Sasha Dees, Dudu, Yi-Ting Wang, Jin Xia, Mr. Cai, Bagus Pandega, Ariel Kuo, Lois Chen, Shanglin Wu, Jing-Sheng Dong, Su-Wei Fan, Wei-Hsiu Wu, Shui-Hui Wu, Mingyuan Chen, Richard Kao, Bo Yu Yao, Chen, Chun-Yin, Joku S, Kun Da Li, Ling Huang, Shan-Yuan Lin. // SWAB Barcelona, Nordisk kulturfond, CLUB9, Ministry of Culture Taiwan, Oficina Económica y Cultural de Taipei, Baik Art Jakarta, National Museum of Natural Science, Nunu Fine Art, A Spring Project, Taipei Botanical Garden, Herbarium of National Taiwan University, Cheeyen Camphor Factory Miaoli.

Bibliography:

- E.Petter Axelsson, F. Merlin Franco. Popular Cultural Keystone Species are also understudied — the case of the camphor tree (Dryobalanops aromatica).Trees, Forests and People (September 2023)

- Faizah Zakaria. The Camphor Tree and the Elephant (February 2023)

- Agus Yadi Ismail, Cecep Kusmana, Eming Sudiana, Pudji Widodo. Short Communication: Population and stand structure of Cinnamomum sintoc in the Low Land Forest of Mount Ciremai National Park, West Java, Indonesia. (April 2019)

- Zhi Yang, Bing Liu, Yong Yang, David K. Ferguson. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cinnamomum (Lauraceae) Ecology and Evolution (October 2022)

- Shu-Miaw Chaw, Yu-Ching Liu, Yu-Wei Wu, Han-Yu Wang, Chan-Yi Ivy Lin, Chung-Shien Wu, Huei-Mien Ke, Lo-Yu Chang, Chih-Yao Hsu, Hui-Ting Yang, Edi Sudianto, Min-Hung Hsu, Kun-Pin Wu, Ling-Ni Wang, James H. Leebens-Mack & Isheng J. Tsai. Stout camphor tree genome fills gaps in understanding of flowering plant genome evolution. Nature Plants (January 2019)

- Rafie Hamidpour, Soheila Hamidpour, Mohsen Hamidpour, Mina Shahlari. Camphor (Cinnamomum camphora), a traditional remedy with the history of treating several diseases. IJCRI (February 2013)

- Jeffrey D. Palmer, Douglas E. Soltis, Mark W. Chase. The plant tree of life: an overview and some points of view. American Journal of Botany (October 2004)

- Taiwan Botanic Database. https://tbd.tbn.org.tw/

- Rohwer, Jens G. “The Status of the Genus Cinnamomum (Lauraceae).” Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society (1986)

- Boomgaard, Peter. Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600–1950. Yale University Press (2001)

- Chang, Jia-Lun. The Investigation and Reforestation of Taiwan. Camphor Tree during Early Japanese Rule. Culture Vision, TAIWAN NATURAL SCIENCE (2016)

- Database of Antei Tashiro in National Taiwan University Library. http://www.darc.ntu.edu.tw/newdarc/darc/index.jsp