Context

展覽概述

In my childhood, the presence of camphor trees was always accompanied by their scent. They were my grandmother’s companions, and the fragrance that drifted from the small white balls in her wardrobe. The smell was slightly pungent, yet not as sharp as mint; over time, it exuded a subtle sweetness. Each time I inhaled it, it felt like being gently embraced by a quiet, stabilizing force.

As I grew up, I realized that camphor trees weren’t just a part of my personal memories; they were deeply rooted in the history of this island, Taiwan. In the city, camphor trees form lines of street trees. Along Dunhua South and North Roads, rows of greenery shift with the seasons; in the 1932 Taipei urban plan, Ren’ai Road was designed as a park avenue, lined with camphor trees. During the Japanese colonial period, Zhongshan North Road, as a path leading to the Shinto shrine, was also accompanied by camphor trees. They are not only the green veins of the city but also witnesses of history..

Camphor trees were once a vital industry that supported Taiwan’s economic lifeline. In the collective memory of many Taiwanese, camphor was a glorious industry of the 19th century. With the invention of smokeless gunpowder, celluloid, and photographic film, the demand for camphor skyrocketed. At one point, Taiwan’s camphor production accounted for 70% of the world’s total, earning the island the title of “Camphor Kingdom” for half a century. This chapter of history gradually closed with the emergence of chemically synthesized camphor.

Historically, camphor trade was highly active. Marco Polo noted that camphor had been exported from Southeast Asia to the Middle East since the 6th century (Polo 1845). Furness (1902) and Nicholl (1979) reported on camphor trade among local communities in China and Borneo. Lundqvist (1949) mentioned the Dayak people trading camphor at Nunokan in Borneo, possibly with Arab merchants. Even in the 1950s, Bornean camphor remained a rare and highly valuable commodity (Césard 2007).

Starting from a non-human perspective and extending into artistic practice, the ecological and migratory experiences of islands have provided me with abundant nourishment. Years of observation and reflection gradually crystallized into the theme of this exhibition:

Camphor Tree Chronicles: Rooted in Elsewhere.

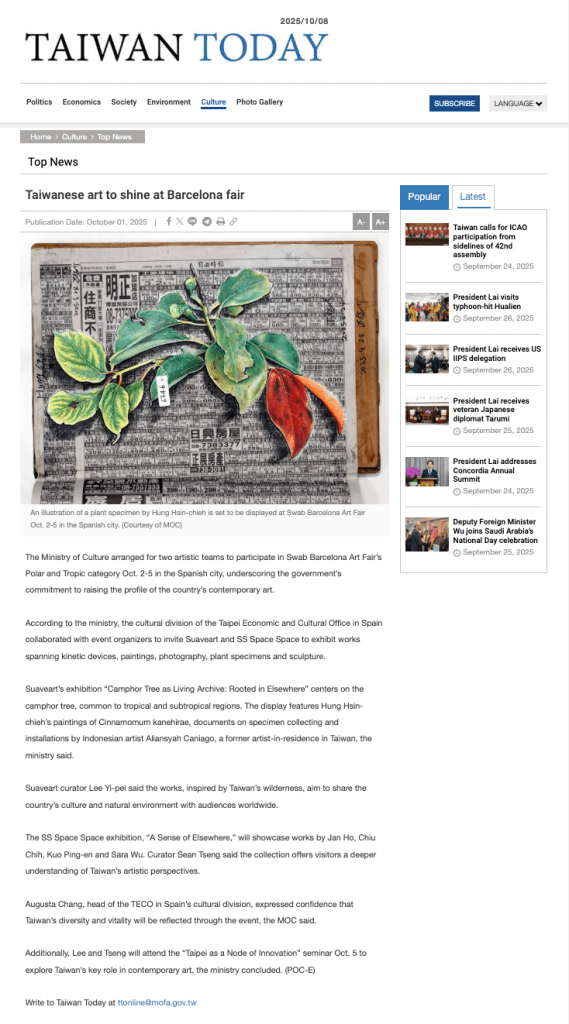

Using a plant commonly found in tropical and subtropical regions—the camphor tree—as a point of departure, I invite viewers to enter the temporal scale of plant memory. By emphasizing “slow time,” the exhibition disrupts the linear tempo of contemporary society, responds to current reflections on the “more-than-human,” and reconstructs curatorial narratives and artistic forms through the lens of the camphor tree.

I view the camphor tree as a living archive. Regarded as the “tree of longevity” in Asia, its life span far exceeds that of a human, allowing it to become a cross-generational and cross-regional witness to memory and history. In 2022, plant taxonomy underwent a major revision: scientists from the Institute of Botany at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing Forestry University, and the University of Vienna, based on DNA phylogenetic analyses as well as features of buds, leaf veins, epidermal cells, and microscopic structures, formally split the traditional broadly defined genus Cinnamomum (s.l.) into two distinct genera: Camphora (Camphor) and Cinnamomum (True Cinnamon). This scientific division mirrors contemporary societal and ethnic reconfigurations.

The exhibition invites Taiwanese and Indonesian artists concerned with camphor trees to reconsider the relationship between plants and the Anthropocene, exploring concepts of locality, colonialism, and diaspora. One narrative traces the disappearance of camphor trees in history and memory, while another safeguards the life of surviving trees. The interweaving of these threads allows us to see how camphor trees traverse colonial histories, scientific research, and artistic creation, becoming a shared core of memory and regeneration.

Curator Yipei Lee and the participating artists pose a mutual question: when we consider human history, migration, and memory through the life cycle of plants, can the hidden cultures and emotions take root once more? In the face of climate change, land crises, and cultural amnesia, can plants serve as alternative witnesses and agents of action?

The Dual Identity of Camphor: Aromatic Confusion and Historical Truth – The scent of camphor not only weaves a tapestry of cross-regional and cross-civilizational aromatic legends but also leaves behind a history full of confusion. In the contextual background, botanically, the camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) is primarily found in southern China, Taiwan, and Japan’s Ryukyu Islands, with its range extending to parts of Southeast Asia. Interestingly, most camphor trees in tropical regions are not native but were introduced in modern times.

On the other hand, the “natural borneol” produced by another plant, Dryobalanops aromatica, has been a precious spice since ancient times. Its main origins are Barus on the west coast of Sumatra and Borneo. Ancient texts from Arabia, India, and China all documented the high value of “Barus camphor,” which was at one point even more expensive than gold.

Although these two are botanically distinct, their extremely similar scents and uses have caused them to be covered by the same name for a long time. In ancient Chinese texts, “camphor” mostly referred to Cinnamomum camphora, while in the Arabic and Malay worlds, the term Kapur Barus specifically denoted Dryobalanops aromatica. The use of a single name to refer to two different plants, this historical “aromatic misunderstanding,” reflects the complexity of cross-regional trade and cultural exchange of “Eastern scents.”

Camphor Tree Chronicles is more than just an exhibition about camphor trees; it’s an exploration into the spirit of plants. Here, plants are no longer mere backdrops. Instead, they act as choreographers, weaving a field of empathy between humans and nature. We are not simply “viewing nature”; we invite you to set aside your preconceptions and, through scent, touch, and sight, resonate with the rhythm of the camphor tree’s life. This is a chance to empathize with nature and co-author a symphony of life that transcends time and species.

Selected Media Exposure:

Curator:

Yipei Lee

Artist:

🌳 Exhibition (Polar-Tropic)

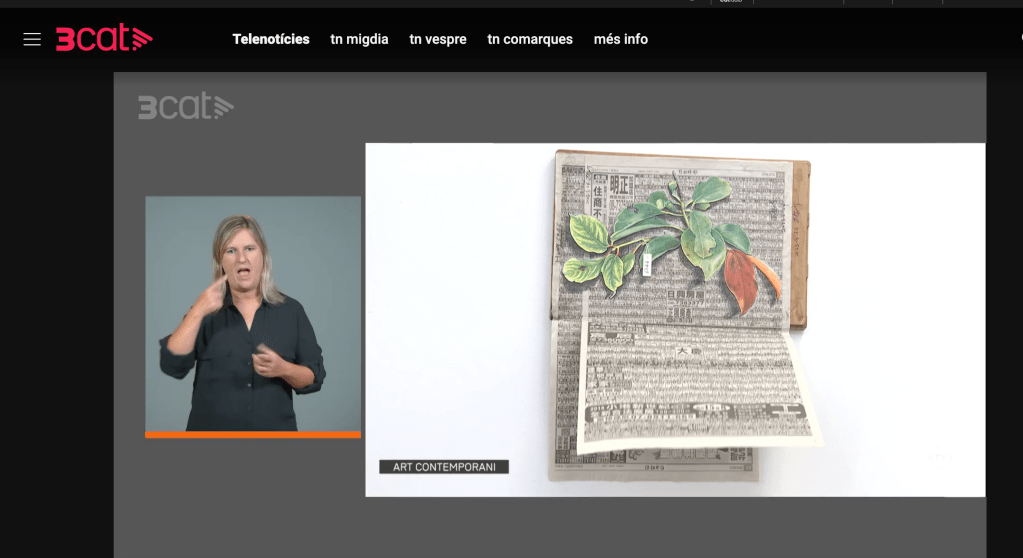

artist works by Aliansyah Caniago, and Hsin-Chieh Hung

***

Activities:

📻 Radio (Station of Commons)

together with Trastienda Machete, PALMADOTZE, AFTERpoema, and SUAVEART

🩷 Poster (lumbung.press & Oksasenkatu 11)

designed by Yipei Lee

📺 Video

shooting in 2018 by Aliansyah Caniago

🔊 Audio

co-created with Jill Zheng, Francis Cai, Xiao Zhang, and Hsin-Chieh Hung

🚶🏼♀️➡️Performance Art (CLUB9 – ARTefACTe)

ZONE X by Evamaria Schaller

***

Photo Credit: SUAVEART and SWAB

Special thanks:

Lorena Tabares Salamanca, Lizette Nin / Tangent Proyectos, Patrick Tantra, Donnin Arifianto, Rico “Obos”, Mesha Gunady, Sasha Dees, Dudu, Yi-Ting Wang, Baik Art Jakarta, National Museum of Natural Science

Supported by

SWAB Polar & Tropic – Nordisk kulturfond, CLUB9 – ARTefACTe, EL ÁGUILA, Ministry of Culture, Oficina Económica y Cultural de Taipei

策展人:

李依佩

藝術家:

🌳 展覽 (Polar-Tropic)

阿里安山・卡尼亞哥、洪信介

***

活動:

📻 電台 (Station of Commons)

Trastienda Machete, PALMADOTZE, AFTERpoema, and SUAVEART 聯合錄製

🩷 海報 (lumbung.press & Oksasenkatu 11)

李依佩

📺 錄像

阿里安山・卡尼亞哥於2018年拍攝

🔊 聲音

鄭文吉、蔡正琨、張曉、洪信介共創

🚶🏼♀️➡️行為藝術 (CLUB9 – ARTefACTe)

ZONE X by 伊娃瑪麗亞・沙勒

***

攝影:細着藝術、SWAB

特別感謝:Lorena Tabares Salamanca, Lizette Nin / Tangent Proyectos, Patrick Tantra, Donnin Arifianto, Rico “Obos”, Mesha Gunady, Sasha Dees, Dudu, 王藝婷, Baik Art Jakarta, 國立自然科學博物館

支持單位:SWAB Polar & Tropic – Nordisk kulturfond, CLUB9 – ARTefACTe, EL ÁGUILA, Ministry of Culture, Oficina Económica y Cultural de Taipei