Introduction

Herianto Sulindro (Kho Lin Hek, born 1928 in Sokaraja, East Java, Indonesia, passed away in March 2025) was a postmodern Chinese-Indonesian architect and urban planner. He received his first architectural training at the Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) in Indonesia before continuing his studies in Delft, the Netherlands, and Berlin, Germany. There he began his professional career as an architect and urban planner. He later worked for the city of Zurich for three decades and also took on architectural projects in Indonesia, Brazil and Switzerland.

In this interview series, SUAVEART speaks with Linda Lochmann-Sulindro (Lindawati Kho), the only daughter of architect and urban planner Herianto Sulindro. Through her reflections, memories, and research, the interviews trace both an intimate family narrative and a broader cultural and professional history.

The conversation unfolds across three interconnected articles.

Article I examines Herianto Sulindro’s migration journey, his cultural identity, and his lived experiences as part of the Chinese-Indonesian diaspora in Europe. This section situates his life within larger histories of displacement, belonging, and transnational movement.

Article II focuses on his professional practice, exploring his long-standing career as an architect and urban planner. Here, attention is given to his working methods, values, collaborations, and the urban contexts he helped shape, particularly within Switzerland.

Article III turns toward what comes next. Following a remarkable career, this final section considers what continues to unfold from Herianto’s life and work. Through the architectural archives and objects he left behind, it articulates the curatorial vision shaping the forthcoming exhibition, as well as the broader approach to preservation and future research.

Part 3

Beyond Practice: Legacy, Research, and Future Making of a Living Archive

After his stellar career, this final section turns to what continues to unfold from Herianto’s life and work. Here, we explore the legacy he leaves behind, the research opportunities that emerge from his archives, and the vision that guides the upcoming exhibition.

These questions address not only how his ideas are preserved, but also how they might shape future generations of architects, researchers, and communities. In this final chapter, we look at how his stories, documents, designs, and memories evolve – opening up new avenues for learning, dialogue, and imagination.

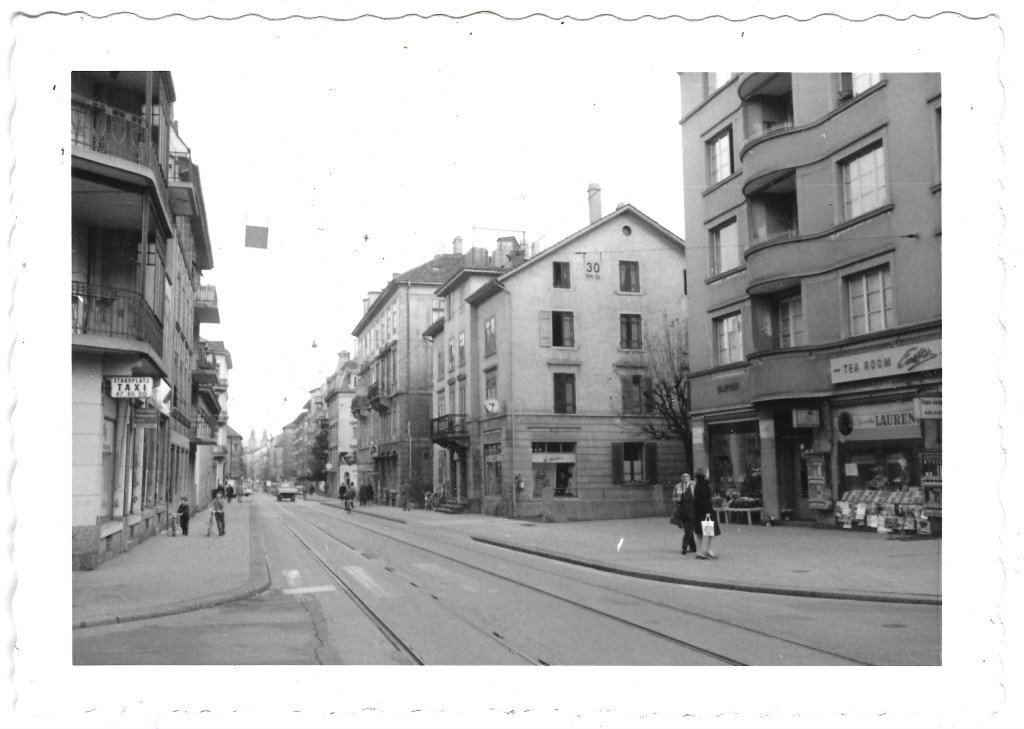

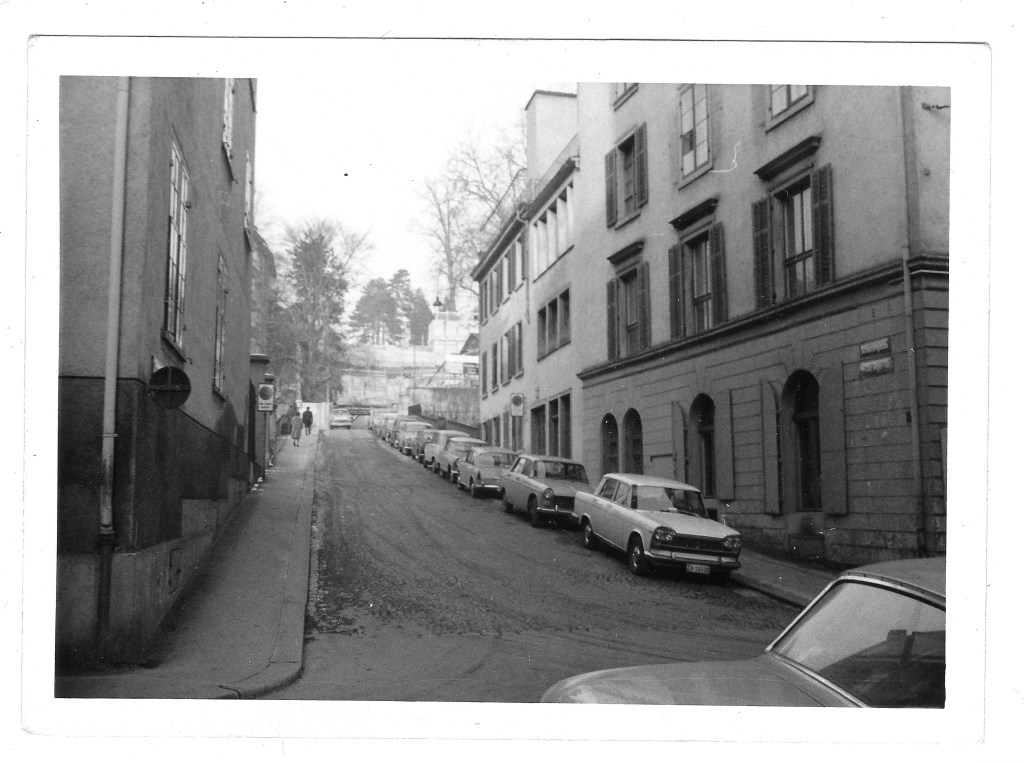

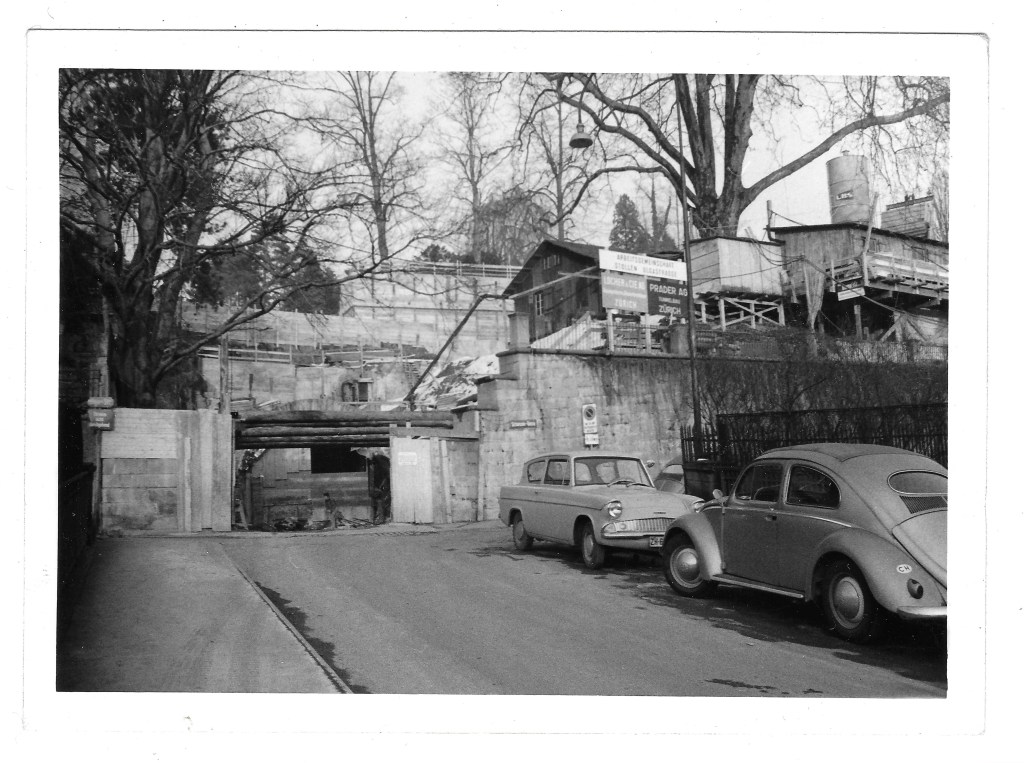

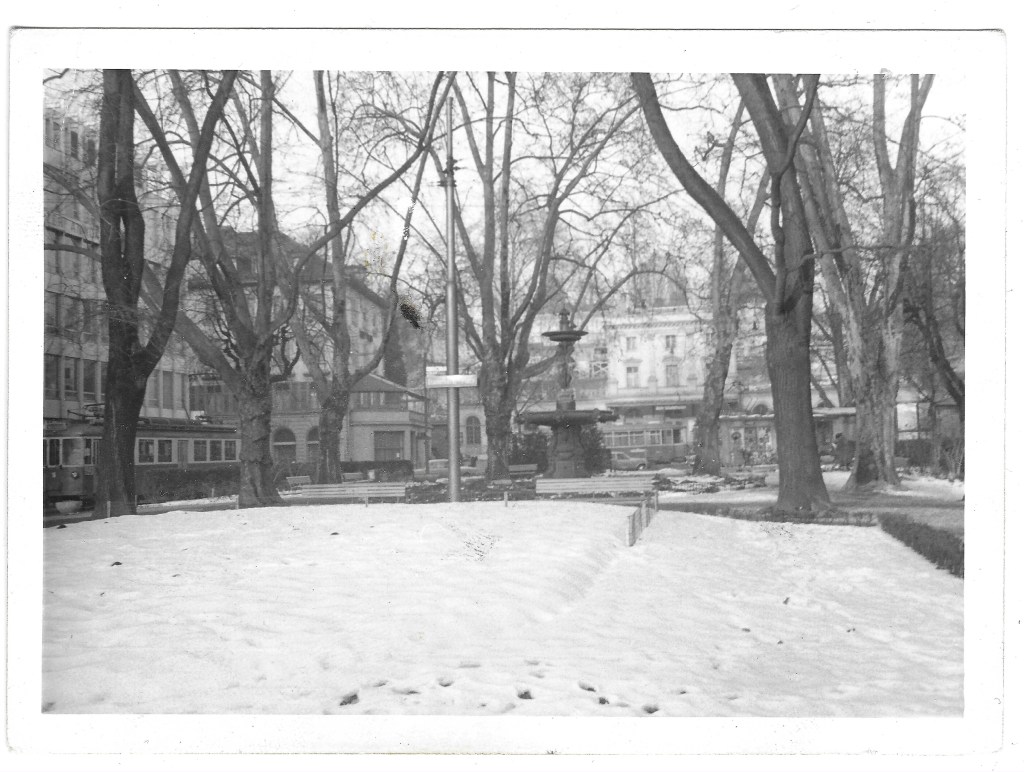

In his spare time, my father often took me on long walks through areas connected to his work as an urban planner. These walks were never random. We followed streets, intersections, parks, and transitional spaces that mattered to him professionally. For me, they became an informal education, an embodied way of learning how cities function, how people move, and how everyday life unfolds within planned environments.

As we walked, he would point out details that might otherwise go unnoticed: the width of a pavement, the way a crossing guided pedestrians, or how a green space softened a dense urban block. These moments were also deeply personal. Walking together created a shared rhythm, a space for conversation, curiosity, and quiet observation. Architecture and urban planning were not abstract topics; they were experienced through movement, presence, and time spent together.

When I retrace these routes today as part of the SUAVEART-led research walks, those memories resurface vividly. The city feels layered with past and present at once. Sensory impressions, such as the smell of fresh bread from a neighborhood bakery or the sound of children playing in a nearby park, trigger emotional responses and recall the warmth and attentiveness of those shared moments. What I experience now is not only the physical structure of the city, but also the emotional geography shaped by walking alongside my father.

These walks have become a bridge between memory, research and conversation. It allowed me to understand his work not only through drawings and archives, but through lived experience. Walking the same paths today carries a quiet sense of continuity, an awareness that urban spaces, like personal histories, are formed through repeated movement, shared time, and enduring presence.

These are complex questions, and I can only respond to them in a necessarily condensed way. My perspective is shaped by childhood and adolescent memories, watching my father work, accompanying him on walks through the city, and much later asking him about specific planning situations and private housing projects. At times, he explained his blueprints to me, offering glimpses into how he thought through urban and architectural problems.

Much of my understanding has deepened only in retrospect. With the support of curator Yipei Lee and her assistant Sharo Liang, I was able to research building plans in the city archives and cross-reference them with drawings and photographs preserved in my parents’ home. This process made visible both the continuity of his thinking and the adjustments required over time.

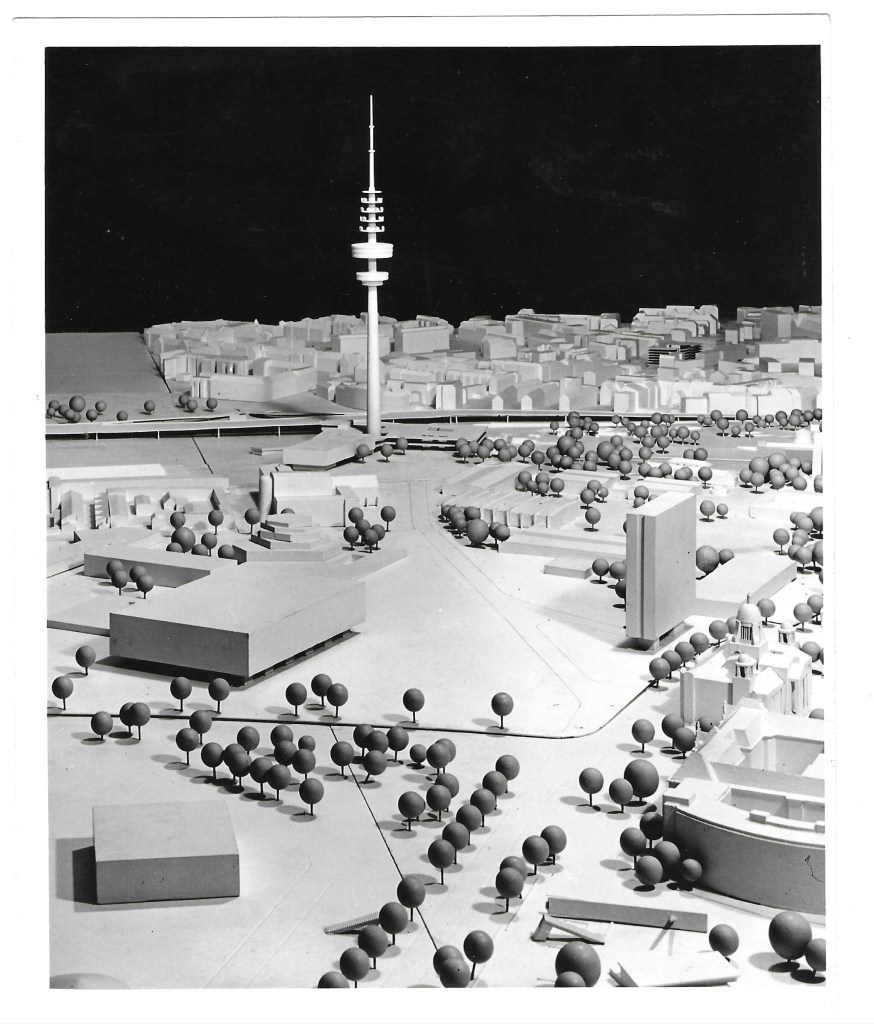

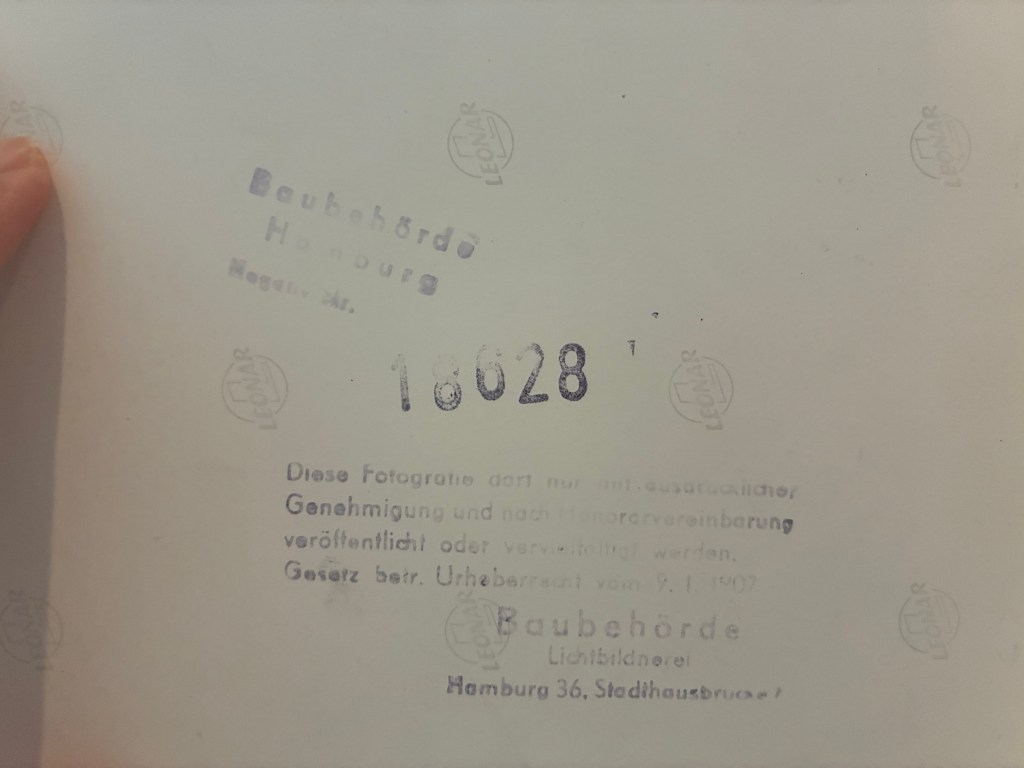

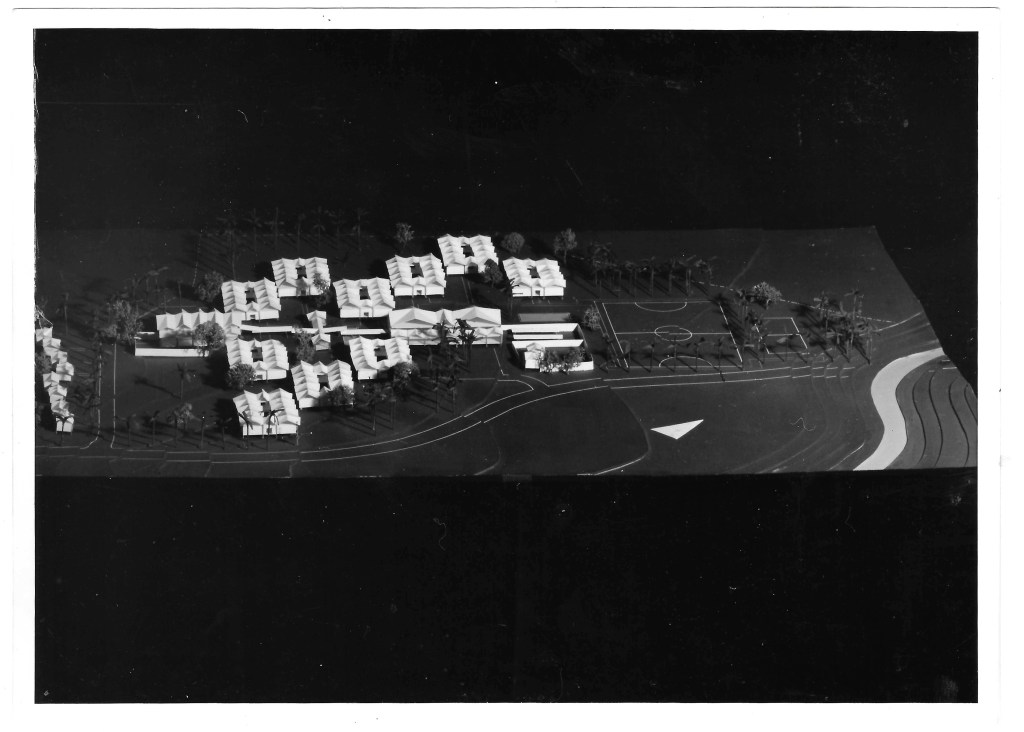

One clear continuity is his ability to adapt to Swiss, and specifically Zurich, urban culture, while still carrying elements of his own background into his work. His drawings reflect principles of Swiss architecture such as clarity, order, and precision, but they are also inflected with sensibilities shaped by Indonesian and Chinese relationships to nature. This is evident in the way streets, squares, and perspectives are composed: open sightline, carefully placed trees and plants, and an emphasis on spatial balance. At the same time, traffic flows, cars, buses, and trams, are meticulously organized to reduce conflict points and improve safety.

Change is most visible in the regulatory frameworks surrounding housing projects. Building guidelines in Switzerland, varying by canton and municipality, are highly strict and have evolved over time. As a result, my father often had to adjust his original construction plans. Even so, several residential projects, such as those in Lufingen, Locarno, and Ascona, were successfully realized, demonstrating his ability to work within constraints without abandoning his core principles.

For me, these routes and projects reveal cities as layered narratives rather than fixed outcomes. What remains is not just physical infrastructure, but a way of thinking about urban space, one that balances movement, safety, and nature. What changes are the rules, uses, and social contexts around them. For future generations, these layers unfold a reading of the city as an evolving archive, where past intentions continue to shape present experience while leaving room for new interpretations and developments.

My father’s approach to designing our home on Schubertstrasse was deeply rooted in Chinese cultural traditions and personal memory. Unlike public projects shaped by regulations and collective needs, the house became an intimate space where he could translate cultural values directly into spatial form. The layout emphasized openness, visual connection, and continuity between rooms.

For example, with the help of friends, he partially removed the wall between the kitchen and the living room, installing a viewing window and an open connection that allowed light, movement, and conversation to flow between the two spaces.

The living room itself was not fixed but evolving. Over the years, it was remodeled two or three times, mainly through changes in the arrangement of sofas, chairs, and the central table. These adjustments reflected his belief that domestic space should remain flexible and responsive to daily life rather than frozen in a single configuration.

Color played an important symbolic role as well. The choice of red and white carpets referenced Chinese tradition and remained unchanged for more than fifty years, even as they became visibly worn. For him, continuity and meaning outweighed ideas of novelty or replacement.

The kitchen was another carefully considered space. Tiles normally used for flooring were deliberately applied to the walls, blurring conventional distinctions between surfaces. The stairway, made of wood and covered with brown carpeting, was designed with particular care and creativity, transforming a functional element into a tactile and warm transition between levels.

Initially, the attic was a large, empty space. During the 1970s to the 1990s, when the house received frequent visitors, my father converted it into three rooms, one workspace and two bedrooms, responding pragmatically to social needs. Later in life, as his health declined, practical considerations became more prominent. Access to sanitary facilities was difficult, with only a small toilet in the basement and a bathroom on the first floor. To address this, he added an additional toilet in the hallway, demonstrating how his design thinking remained attentive to bodily needs and changing life circumstances.

In contrast, his residential projects in Indonesia and Brazil were shaped less by his own cultural references and more by the wishes of others, his nephews, his older sister, and an Indonesian friend. These houses were tailored to local climates, cultural habits, and personal preferences, resulting in solutions that differed markedly from those of our family home. While the Schubertstrasse house reflects his inner world and traditions, the homes abroad reveal his adaptability and sensitivity to the diverse cultural and personal contexts of those for whom he was designing.

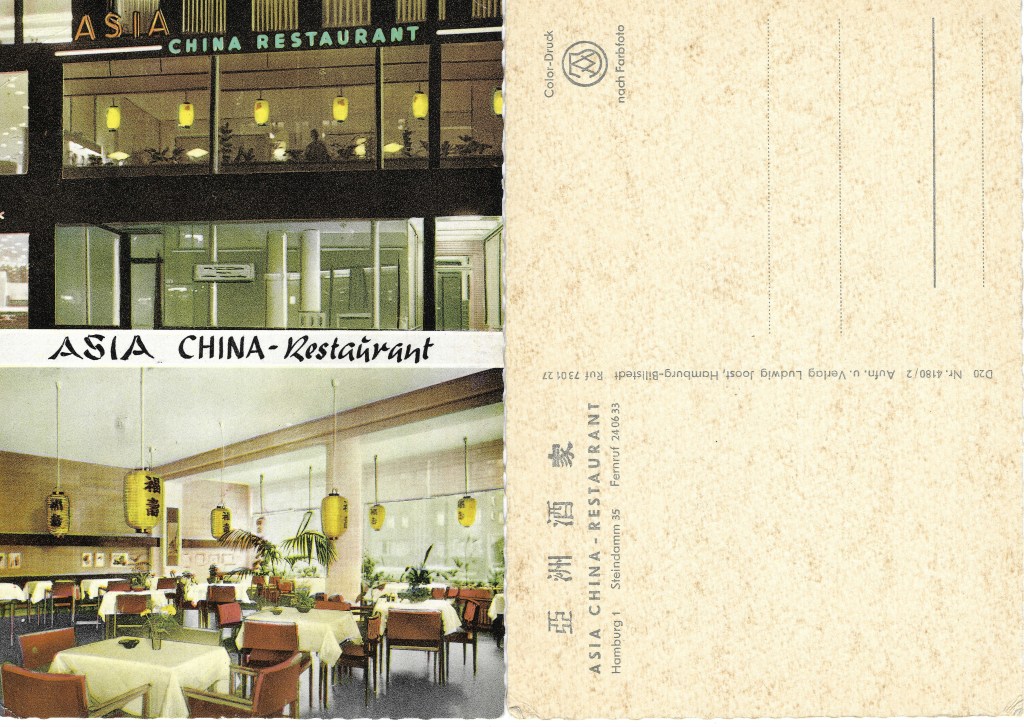

In my parents’ home, the kitchen was the true center of family life.

It was where we spent the most time together and where daily routines naturally turned into shared moments. My mother prepared a wide range of dishes there, Chinese and Indonesian specialties alongside Dutch cakes, such as marble cake. Cooking was rarely a solitary activity. When visitors came, conversations unfolded around the kitchen table while she prepared lunch, turning the space into a place of exchange, warmth, and hospitality.

After the food was ready, we moved into the living room for shared meals. These moments often marked a shift from casual conversation to deeper dialogue. Languages blended naturally, Indonesian and Dutch were used interchangeably, reflecting the layered cultural reality of our family life. The living room thus became a space not only for eating, but for storytelling, discussion, and the quiet negotiation of multiple identities.

Books were another important carrier of culture, though they were not gathered in a single, formal library. Most were stored in an old cupboard in the attic, while a smaller selection was kept on a wall shelf in the living room. The attic collection consisted largely of architectural books from my father’s studies in Delft and Berlin, along with technical manuals on building materials that he had used in his design work. This space felt more private and reflective, closely tied to his professional world.

In contrast, the books in the living room were more practical and outward-looking. They included dictionaries and a thick volume detailing travel routes across Europe, describing where one could go by car. Together, these books mirrored the dual orientation of our home: inward toward study, work, and memory, and outward toward movement, travel, and connection. Through these everyday spaces and objects, culture was not taught explicitly, but lived, absorbed through shared time, language, food, and presence.

Our family life largely unfolded in the kitchen, where my mother took care of cooking and housekeeping. It was the heart of the home: the place where daily conversations happened and where we most often ate together. At times, we moved into the living room to relax and exchange ideas more quietly. I, on the other hand, often retreated to my own room, doing homework or reading.

Culture was transmitted in our household primarily through shared meals and conversations. The kitchen played a central role in keeping traditions alive, as recipes and cooking practices from our cultural background were passed down almost naturally, through repetition and presence.

Beyond the home, my father also actively nurtured this sense of cultural continuity. He frequently took his siblings, as well as my mother’s siblings, to visit scenic places, introducing them to the beauty of the surrounding landscapes. On some occasions, he even rented a bus so that extended family members could travel together. These shared journeys strengthened family bonds and reinforced a collective sense of belonging.

One particularly meaningful legacy I inherited from my father is a passion for photography. We were both enthusiastic photographers, documenting our travels and everyday moments. These photographs are more than personal souvenirs; they form a visual archive of our family’s cultural life and mobility. Among the objects preserved in our family archive are my parents’ Indonesian passports, which I still keep today. They bear witness to decades of travel, having been renewed several times at the Indonesian embassy in Switzerland, and containing visas from numerous countries they visited.

Although my parents lived in Switzerland for over fifty years, they were twice asked by the Zurich registry office whether they wished to acquire Swiss citizenship. For various reasons, they chose not to do so, as they did not want to relinquish their Chinese-Indonesian traditions or their sense of belonging to Indonesia. Until their deaths, they maintained close relationships with siblings and extended family members living not only in Indonesia but also in other countries shaped by migration.

Domestic spaces, and the objects and practices embedded within them, reveal a great deal about how migrant families transmit cultural identity across generations. The kitchen, as a space of encounter, nourishment, and exchange, embodies both continuity and adaptation. The memories and experiences formed in such spaces foster a sense of belonging and play a crucial role in shaping and sustaining identity in a new cultural context.

Thanks to the initiative of the German curator and architectural scholar Eduard Kögel, and the generous support of my cousin Melani Setiawan in Jakarta, I decided to take responsibility for my father’s family and architectural archive. This decision became the foundation for two major architectural exhibitions: one at Taman Ismail Marzuki in Jakarta and another at the Technical University of Berlin. Both exhibitions were organized by SEAM Encounters in collaboration with Indonesian architects, with my active involvement, and presented the works and life’s oeuvre of my father, Herianto Sulindro.

I am deeply proud that, only a few years ago and despite his advanced age, my father received international recognition as a postmodern Chinese-Indonesian architect. With his consent, I have continued to develop and care for the archive, with the aim of preserving his artistic and architectural legacy and making it accessible for scholarly research.

The archive has since grown into a substantial body of material, encompassing architectural drawings, photographs, personal documents, correspondence, and exhibition-related materials. Through ongoing collaborations with German and Indonesian architects, as well as with the Taiwanese curator Yipei Lee (SUAVEART), I continue to learn while actively contributing to the expansion of this curatorial and artistic research.

Looking ahead, I see Herianto’s archive as a vital resource for deeper research into transnational architectural histories, postcolonial modernism, and cross-cultural design practices. It offers a strong foundation for shaping future curatorial frameworks and developing exhibitions that address migration, identity, and knowledge transfer across generations. Making the cultural significance and long-term value of this archive visible is not only a professional commitment, but also a personal responsibility.

Archives are more than documents — they are living memory.

A more intimate and layered view.

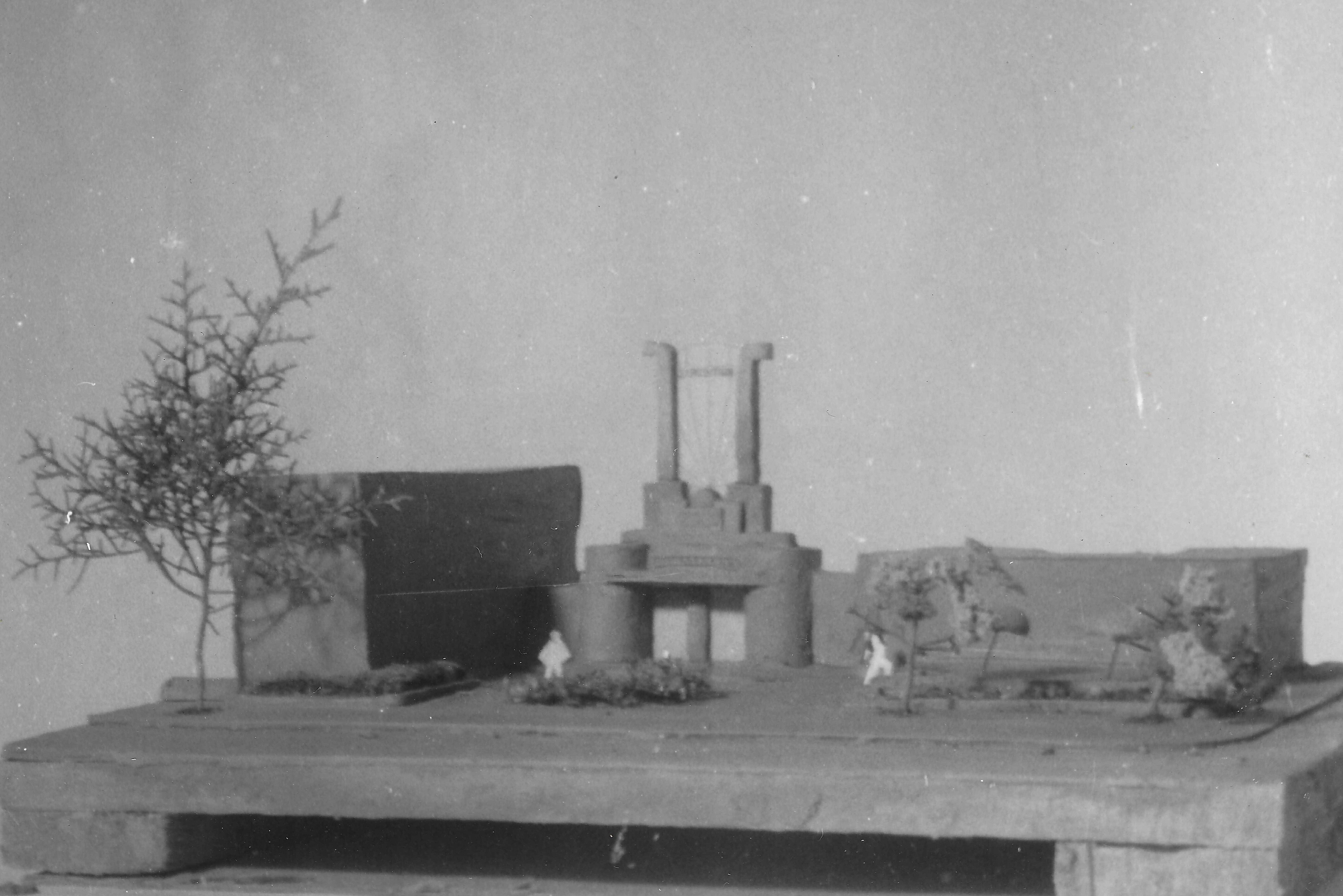

My father’s work has already been presented in Jakarta, Germany, Zurich, London, and most recently in Shanghai. Each exhibition revealed a different layer of his practice, shaped by its local context and by the people involved. Building on these experiences, the upcoming exhibition is conceived not as a retrospective in the traditional sense, but as a living archive, one that continues to unfold.

In October 2025, a smaller exhibition took place in Shanghai with the support of curator Yipei Lee and Chinese artist Jill Zheng. Jill had previously worked on The Invisible Trajectory at my parents’ house in 2024, responding poetically to the spatial arrangements of the domestic environment. In both Zurich and Shanghai, she presented artist poetry as a spatial response and supported guided walks through my father’s urban works. These collaborations, rooted in attentiveness and care, deeply shaped how I now think about exhibition-making as something experiential, embodied, and dialogical rather than purely informational.

My experiences in artist-in-residency contexts, and working closely with Caroline Ip, Arne Schmitt, and Jill Zheng, reinforced the importance of slow research, trust, and shared presence. Their feedback and ways of working encouraged me to think beyond static displays and towards exhibitions that invite visitors to move, listen, read, and feel, much like walking through a city or a home shaped over time.

Looking ahead, it is very important to me to present my father’s work in multiple locations in Indonesia, including Jakarta, Bandung (ITB), and Sokaraja — his birthplace and the site of the current parental home. These places are not merely exhibition venues; they are part of the story itself.

I envision the next major exhibition, planned for Jakarta, will pay homage to his three-decade career in architecture and urban planning. Unlike earlier exhibitions, this one will offer a more intimate and detailed view of his archive, tracing his early beginnings, professional practice, and the broader significance of his contributions within global architectural and urban histories.

The exhibition will also situate my father within the wider context of the Kho family, whose cultural and intellectual legacy continues through his siblings and relatives in Indonesia and beyond. This familial network, spanning architecture, medicine, art, and sports, reveals how knowledge, discipline, and cultural values travel across generations and geographies.

Visitors can expect to encounter architectural drawings, photographs, personal documents, objects, and artistic responses woven together with stories of migration, education, and resilience. I hope the audience comes away with a deeper understanding of why a first-generation Chinese-Indonesian architect chose to study and work abroad, how he navigated multiple cultural worlds, and what it meant to build a meaningful architectural career across continents.

Ultimately, I hope the exhibition invites reflection on architecture not only as built form, but as lived experience – shaped by family, movement, memory, and the quiet persistence of cultural identity over time.

That is a very important and timely question. As Herianto’s only daughter, I am responsible for both the family and architectural archive, a role I carry out in accordance with my father’s wishes and in close agreement with my cousin Melani Setiawan, the daughter of my father’s older sister, Kartika Sulindro (Kho Siok Lie).

My ongoing collaboration with SUAVEART, together with my close working relationship with the German curator and architectural scholar Eduard Kögel, has made it possible to access and contextualize building plans, documents, and photographs. At the same time, the digitization of this material remains a significant challenge due to the scale and complexity of the archive. I am deeply grateful to Yipei Lee and Sharo Liang for having already digitized several key documents, which has been an essential first step.

While I hold the responsibility for this archive, it is clear that its long-term preservation and accessibility cannot be achieved alone. I am actively seeking support, both institutional and collaborative, to continue the digitization process and to develop sustainable ways of sharing this material with a wider audience. Equally important to me is the continued realization of exhibitions that allow my father’s architectural and cultural legacy to be encountered in physical space.

Looking ahead, the establishment of a foundation is a goal I strongly wish to pursue as his heir. Financial support and donations would play a crucial role in enabling future exhibitions, research initiatives, and publications, ensuring that my father’s work remains accessible, meaningful, and open to future generations.

Eventually, this archive is not only about the past. It is about how stories, spaces, and knowledge continue to travel, long after a person is gone.

The immediate priority has been the relocation of archives from my parents’ house, which took place between October and December 2025. With the help of Yipei Lee, a close friend and collaborator, I packed the archival materials and transferred them to my condominium in Hittnau. Because space there is limited, the archive is currently stored in the guest room and partly in the basement. This is not ideal, but it is the only workable solution for now.

Looking ahead, my goal is to create a dedicated space with two closely connected functions: a place to live and a large shared hall that can serve as both archive and working space. This hall would allow for proper storage, digitization, cataloguing, and research, with tables and equipment set up for ongoing use. Rather than keeping the materials boxed away, I want the archive to remain active, open to study, reflection, and curatorial development. I see this as a practical and meaningful way to care for the archive.

To make this vision sustainable, establishing a foundation is an important next step. A formal structure would allow me to seek long-term support and collaboration, and to ensure that the archive can be responsibly maintained and shared. For me, this is not only a logistical decision, but a personal commitment to preserving my father’s legacy as a living resource for future generations.

I invite everyone reading this article to continue exploring these narratives and to engage with our ongoing exhibitions and projects alongside us.

【Cities, as seen through the lens of Herianto Sulindro】

Bali visit around early 1950s, — by Herianto Sulindro

Parkhotel Thordsen view from the east — by Herianto Sulindro, Hamburg

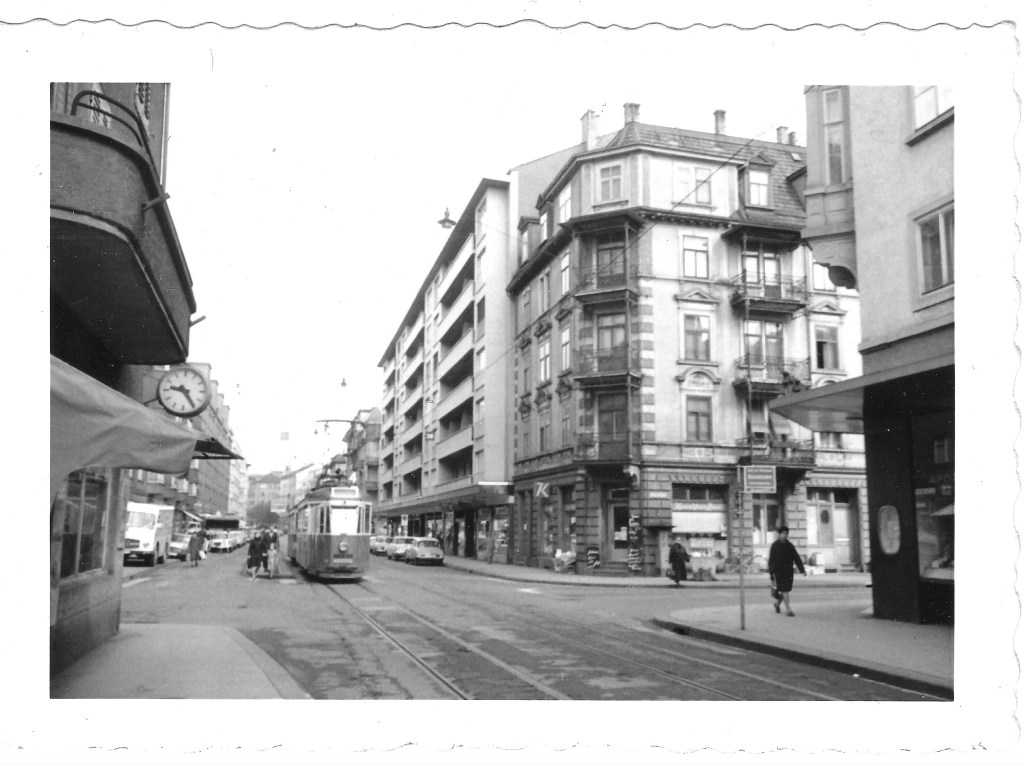

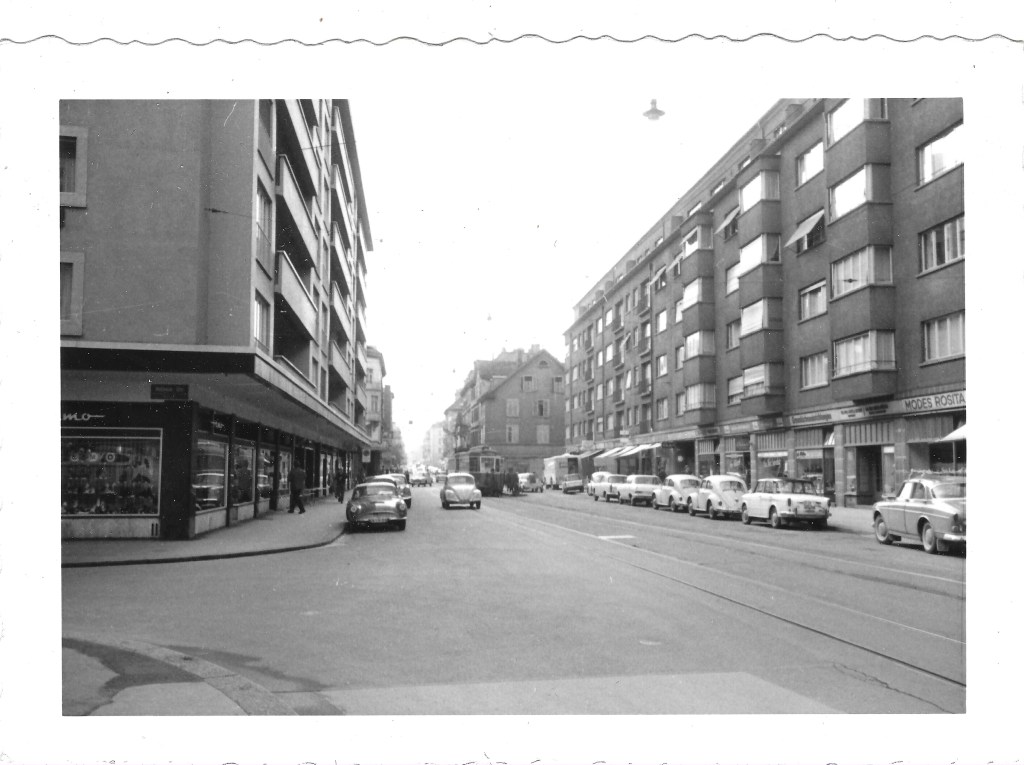

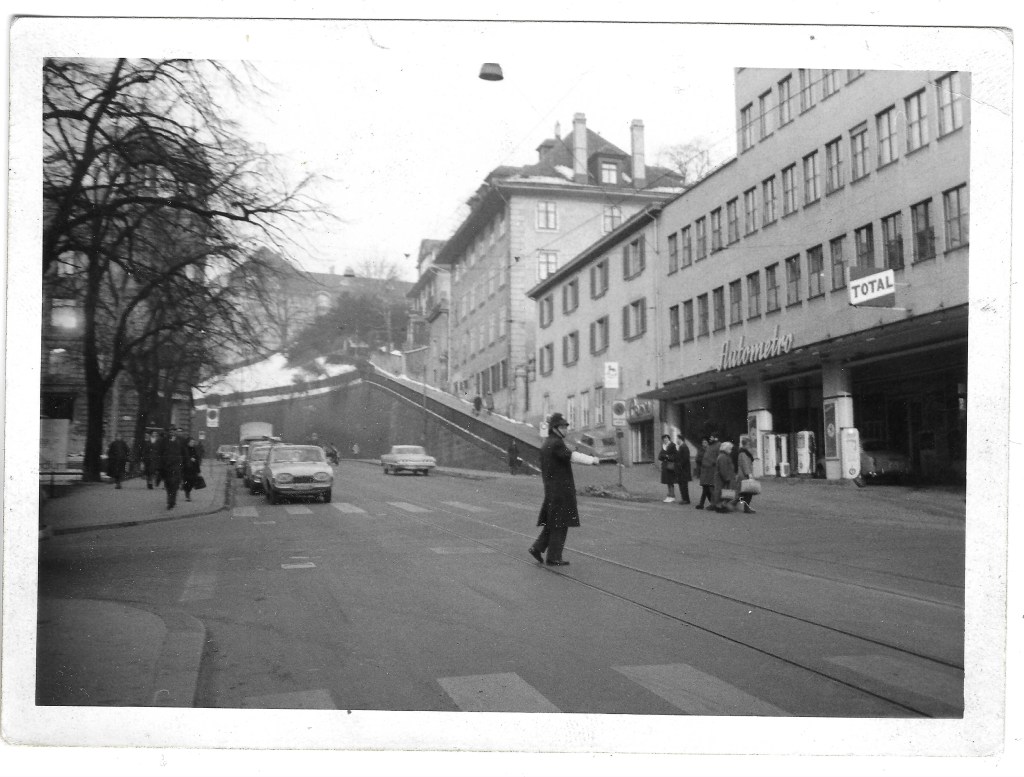

Photos taken around Holbeinstrasse – Stauffacherstrasse, Zurich — by Herianto Sulindro

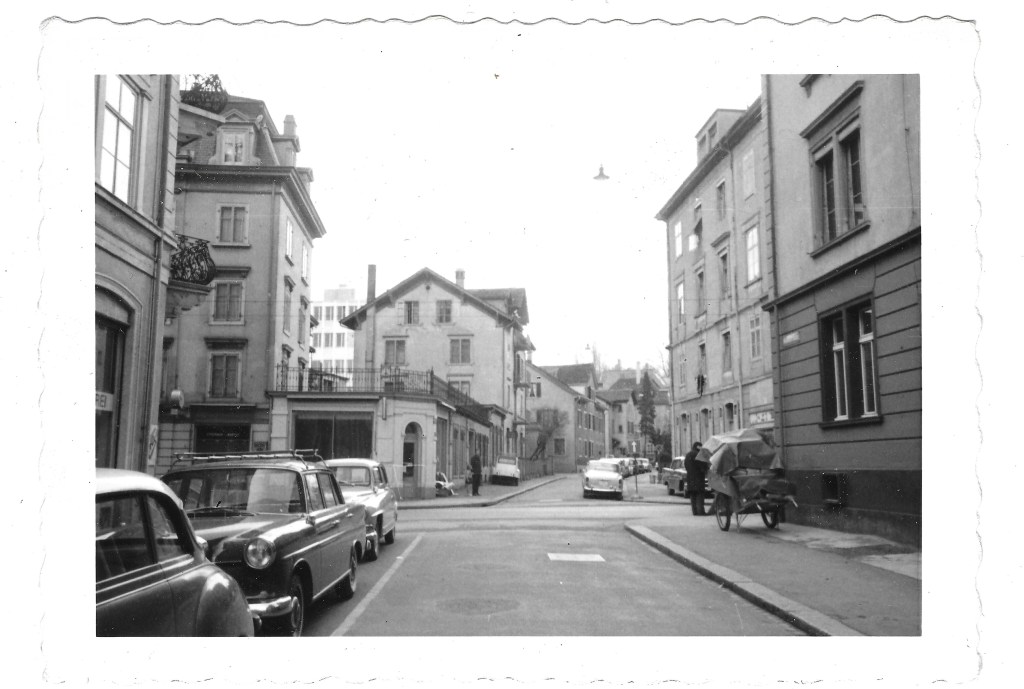

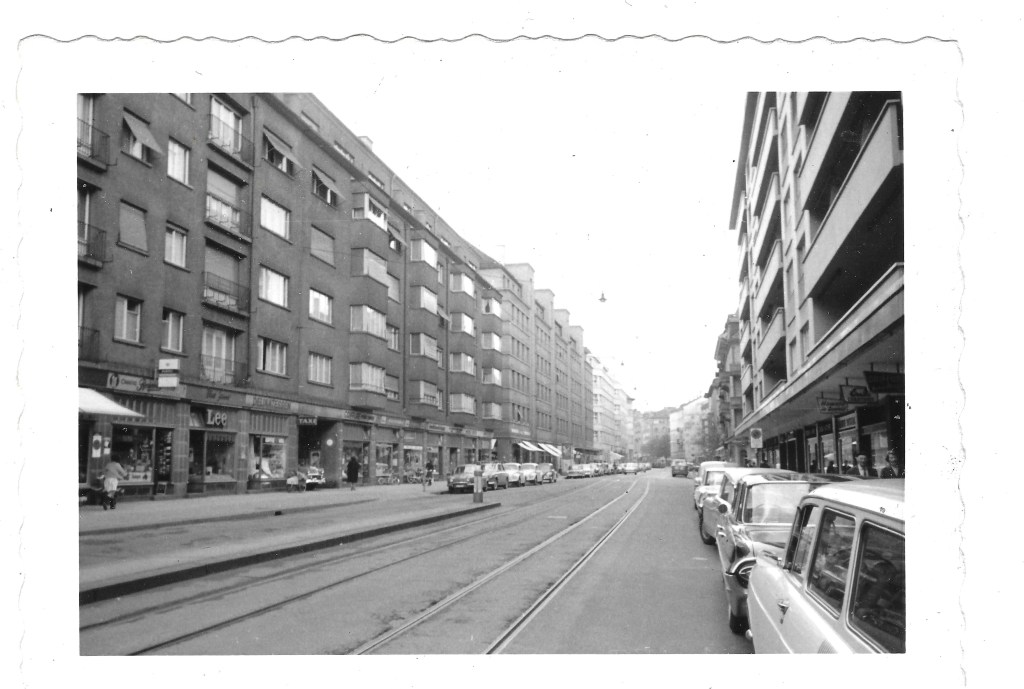

Photos taken around Kreuzbühlstrasse – Schaffhauserplatz, Zurich — by Herianto Sulindro

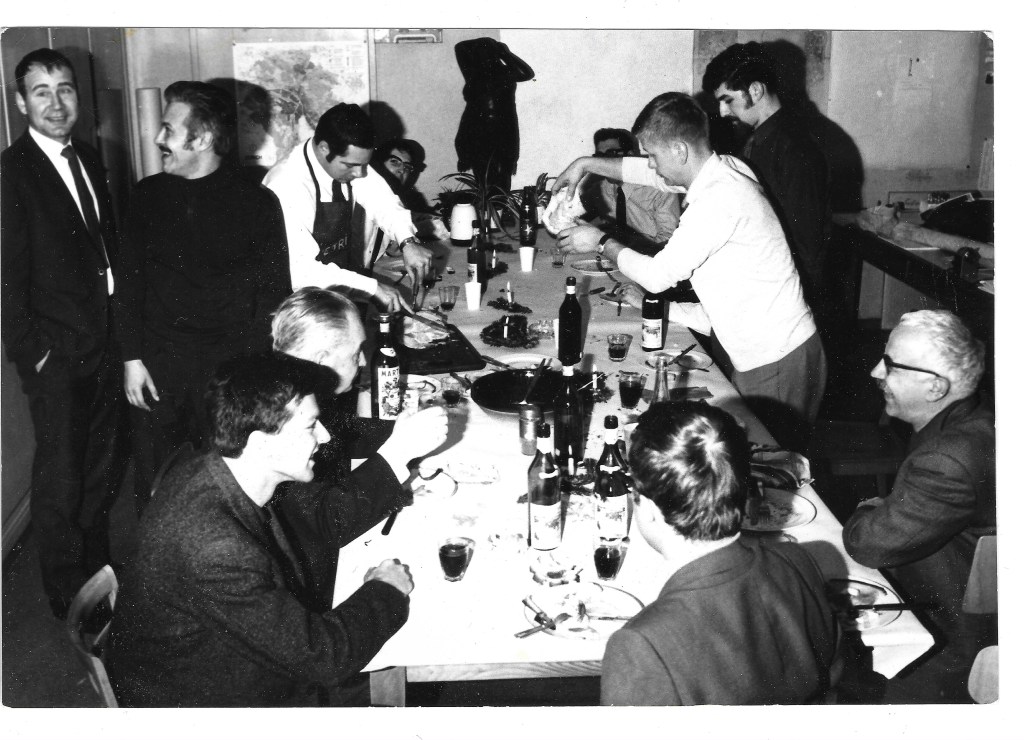

Office colleagues in Zurich, c. 1980s — by Herianto Sulindro

Interviewer: Mesha & Yipei Lee

Special thanks: Linda Lochmann-Sulindro

Photo credit: Linda Lochmann-Sulindro & Kho Family