I am a cultural practitioner who frequently travels to Indonesia, with long-standing attention to its contemporary art development, natural landscapes, socio-economic changes, diverse identities, rituals, and traditional culture. Over the past sixteen years, I have visited many cities—Aceh, Medan, Semarang, Bogor, Cirebon, Surabaya, Yogyakarta, Solo, Malang, Bandung, Bali, Jakarta, and more—experiences that have taken me from mountains to seas, and across islands.

Each time I learn something new, I feel that my understanding of this place’s culture and every visit becomes a fresh experience. As I absorb these fragments of knowledge, they weave themselves into an ever-expanding web in my mind, making it less easy to tell a single, simple story.

But today, I am triggered by the photos and want to share some stories from a place I have quietly followed for years.

Life’s journey itself is a wondrous thing, and serendipity is always part of that fortune.

*

First, let me briefly introduce a friend—let’s call him J. He is an Indonesian of Chinese descent, with a background closely tied to art and architecture. Through his passion for collecting historical objects, he preserves the tangible presence of the past. In his previous projects, he has explored Peranakan culture, Chinese architecture, and objects spanning from the Dutch colonial era to modernist times.

Around 2020, J became involved in the demolition of a building project in Sokaraja, Central Java. The building belonged to a powerful local Chinese-Indonesian family. At the time, he sent me several photos, asking me to help identify the content, calligraphic style, and possible date of a few inscribed plaques, as well as any related history I might know.

In 2022, SUAVEART happened to initiate a research project on a visionary Chinese-Indonesian architect Herianto Sulindro—whose hometown, by coincidence, was also Sokaraja, the place J had once visited. Herianto’s home was not far from the demolition site J had worked on. Since then, J and I have often exchanged stories and histories about the Chinese-Indonesian community.

In July 2025, during my visit to Bandung and stop at ITB, J brought me three pieces of material that thrilled me to the core: one was a record of the demolition process of that building; another, a Western-style portrait of a Chinese gentleman dressed in late Qing / early Republican attire; and the third, household registration documents from the brief Japanese occupation of Indonesia after the end of Dutch colonial rule.

I was deeply moved by these three packages of item—centuries of Chinese-Indonesian cultural, identity, and historical flows, all condensed into one moment, now laid before my eyes.

我是一個經常往返印尼,長年關注著這裡的當代藝術發展、自然景觀、社會經濟變化、身份多樣性、宗教習俗與傳統文化等等的文化工作者。過去的 16 年裡,到過不少城市,像是亞齊、棉蘭、三寶壟、茂物、井里汶、泗水、日惹、梭羅、瑪朗、萬隆、峇里島、雅加達等。或多或少涵蓋了上山下海出島的經驗。

每當我學習到新的知識,便覺得我對這裡的文化認識與每一次的拜訪都是新的體驗。這些知識吸收後,就在我腦中像蜘蛛網一樣,越織越大張,漸漸地不是那麼輕易說出故事。

不過,今天我被一些照片觸動了,想跟大家分享一個多年關注的地方小故事。

生命旅程本身就是一件非常神奇的存在,緣分也是幸運的一部分。

*

首先,我想先稍微介紹這位朋友 J (化名),他本身是印尼華裔,背景主要跟藝術建築相關,藉由收藏老件的興趣保存歷史的存在感。在他過去的項目中,涉略不少 Pranakan 文化、華人建築、以及荷蘭殖民時期至現代主義相關的物件。

約莫在 2020 年前後,他參與到中爪哇 Sokaraja 城市中某一幢建築物的拆遷過程。這幢建築物屬於當地一位有權有勢的華人家族。當時,他寄來幾張照片,請我辨別幾塊匾額的內容、書寫形式、年代以及我可能知道的相關歷史。

2022年,細着藝術 SUAVEART 正好啟動了一位印尼華裔建築師老爺爺 Herianto Sulindro 的研究計畫,而他的家鄉恰好也在 Sokaraja-正好是J 曾經拜訪過的地方。而老爺爺的家離他參與的遺址現場不遠。於是,在過去的時間裡,我們經常交流關於印尼華人的歷史與發生過的故事。

2025年7月,這趟來到萬隆,走訪 ITB 的同時,J 帶來了三份讓我非常興奮的資料!一份是關於建築物的拆遷過程記錄、一份是身著晚清/民國初期服飾的中國紳士西式肖像畫、另一份是印尼華人在荷蘭殖民結束後,短暫被日本人統治的戶口文件。我被這三份資料深深地觸動:華人經過幾世紀的文化、身份和歷史的流動,今日竟然濃縮在一塊,出現在我眼前。

***

Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

Living Spaces Before Demolition

During the period of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) colonial rule, Chinese trade whithin the Indonesian archipelago was thriving. To maintain control over the islands, the Dutch established a rigid social hierarchy in which the Chinese community was not only required to pay taxes but also tasked with managing the local indigenous community. This hierarchical system would later become one of the underlying causes of the anti-Chinese riots after Indonesia’s independence.

In the 19th century, Chinese communities living on Java were highly mobile and radical. Many Chinese traders would travel from the port of Batavia to Sokaraja in Central Java. At the time, several industries flourished around the region, including tobacco (see Cigarette Girl | Official Trailer | Netflix), sugar production, and timber.

Colonial Architectural Remnants

The Dutch colonial presence in Indonesia spanned approximately 350 years—from the early 17th century until 1949—during which they expressed their nationalism through architecture, leaving behind many distinctive examples of colonial-era buildings. These structures blended European (particularly Dutch) classical elements, neoclassical style, and modernist influences, while adapting to local materials, climate, and aesthetics to form a unique Indonesian architectural identity.

Common styles included Dutch Colonial Style, characterized by thick masonry walls, wooden louvered shutters, steeply pitched roofs (often with terracotta tiles), high ceilings, and wide verandas. The Indo-European / Indische Stijl combined traditional Javanese architectural features—such as joglo roofs and open verandas—with European construction techniques, maintaining Dutch aesthetics and sense of order while adapting to the local climate and cultural context.

Art Nouveau / Art Deco style also made their way into Indonesia, marked by ornamental curves, geometric patterns, and streamlined forms. In public buildings, fortifications and civic structures typically displayed heavy stone walls, simple symmetrical layouts, arches, and small windows—emphasizing defense and authority.

推倒之前的居住空間

當時,在荷蘭東印度公司 (VOC) 殖民期間,華人的貿易事業是非常蓬勃的,荷蘭人為了統治印尼群島,建立社會階級制度,使得華人不僅需要繳稅,還需要承擔管理地方土著的責任。這也是造成獨立後排華事件的原因之一。

19 世紀期間,在爪哇島上生活的華人,移動狀態不僅活躍,移動範圍也如鐵路網絡般輻射。許多華人會從巴達維亞港口前往中爪哇 Sokaraja,當時有幾個著名興盛的產業,像是菸草 (推薦看Cigarette Girl | Official Trailer | Netflix)、糖業、木材業。

殖民建築物的殘影

荷蘭人對印尼長達 350 年 (約 17 世紀初到 1949 年) 的殖民統治期間,將民族主義體現在新建築上,留下許多典型的印尼殖民時期建築。其融合了歐洲 (特別是荷蘭) 古典建築元素、新古典主義風格、現代主義,並與當地材料和氣候適應揉雜出獨特的印尼特色的現代建築。

主要常見的有荷蘭殖民風格 (Dutch Colonial Style),特徵是厚牆、木百葉窗、大斜屋頂 (常用紅瓦)、高天花板、寬門廊。印尼-歐洲混合風格/印度風格 (Indo-European / Indische Stijl),特徵是融合爪哇傳統建築元素 (如 joglo 屋頂、開放式走廊) 與歐洲結構技術,保留荷蘭的審美與秩序感,又考慮當地氣候與文化。

此外也有新藝術與裝飾藝術 (Art Nouveau / Art Deco) 的潮流傳入,曲線花飾、幾何線條、流線造型都很常見。在公共建築風格上,則能觀察到軍事與行政建築 (Fortifications & Civic Buildings) 的特徵是厚重石牆、簡潔對稱設計、拱門和小窗,強調防禦與威嚴感。

J told me that the previous owner of this architectural complex was a Chinese-Indonesian, possibly someone whose family had migrated here as early as the Qing dynasty. The site showcased not only Dutch Colonial and Indo-European styles, but also architectural features and interior layouts distinctive to traditional southern Fujian (Minnan) Chinese houses. Along the side of the lower colonial building at the front, there was an open courtyard as well as a Chinese-style facade.

In the next photograph, the front ground-floor building can be seen with stonework, tin awnings, wooden elements, and stained glass. Behind the wall, partially visible, stood a two-story structure: the ground floor in a Western style, the upper floor built with timber and woven bamboo panels.

J 與我分享到這片建築群的前地主是印尼華人,可能是清朝時期就遷徙過來的。而建築不僅可以看到荷蘭殖民風格、印尼-歐洲混合風格,還能看到傳統閩南地區華人特有的建築外觀與室內空間佈局。在前面較矮的殖民建築的側面,除了有空曠的空地,還有中式門面結構。

下一張照片可以看到前面的一樓建築有石材、鐵皮雨遮、木料、彩色玻璃。隱約看到圍牆後面,還有一棟兩層樓的建築,一樓是西式風格,二樓是木材和竹編織物。

From a Western architectural perspective, in terms of Western architecture, this building is defined by its solid stone balustrades and columns, embodying the neoclassical emphasis on symmetry, clean lines, and classical orders. The balustrade’s columns and square decorative motifs are common ornamental elements in classical architecture, symbolizing stability and order. The mouldings on the column bases and capitals imitate classical styles, but with simplified forms better suited to the tropical climate and the construction materials available at that time.

Although the division of indoor spaces and interior details could not match the grandeur of royal or aristocratic residences, the house was still larger than most Chinese or local homes in the surrounding area. Its intricate and refined architectural elements suggest, indirectly, the considerable wealth and social standing of this Chinese owner—status that should not be underestimated in the historical context of the time.

以西式建築而言,這棟建築以沉穩的石材欄杆與柱子裝飾為主,展現出新古典主義注重對稱、簡潔線條以及經典柱式的特徵。欄杆上的柱子和方形裝飾符號,是古典建築中常見的裝飾性元素,代表著穩重與秩序。柱基和柱頭上的線條修飾,仿照古典柱式,但造型簡化,適合熱帶氣候及當時建材條件。

此外,室內空間數量的切割與細節雖無法與皇室貴族規格媲美,卻也比大部分華人或周圍的本地人擁有更大的住宅範圍。其複雜交錯且精緻的建築元素,可間接推敲出這位華人的身家地位,在當時的社會背景是不容小覷。

Flooring Patterns

The interior flooring features typical geometric encaustic cement tiles, a design frequently found in Peranakan or wealthy merchant homes in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), British Malaya, and Singapore.

The low-gloss, geometric-patterned terrazzo tiles are characteristic of Dutch East Indies and early Indonesian architecture from the 1920s to 1940s. The pigments, derived from minerals, penetrate the tile and are resistant to fading. Popular “floral tiles” of the era were often produced by local workshops following European designs, and such patterns were commonly used in colonial-era Peranakan houses or Indo-European style interiors.

The tile layout is framed first by a solid dark-grey border, followed by a band of black Greek key (meander) motifs on a light-grey background. The Greek key, a recurring element in colonial-era floor design, symbolizes continuity and eternity. The central field consists of a light background with dark-grey diamond patterns, with each intersection marked by a four-petal yellow floral motif. This combination of geometric shapes and small floral accents reflects a European sensibility while incorporating local aesthetics—the floral form may have been inspired by Javanese or Balinese motifs.

地板花紋

室內地板花紋採用了典型的幾何馬賽克瓷磚 (encaustic cement tile) 設計。尤其在東南亞的荷屬東印度 (印尼)、英屬馬來亞和新加坡的土生華人 (Peranakan) 或富裕商宅裡面常見。

表面光澤度低的幾何圖案的水磨石磁磚 (terrazzo tiles),屬於典型的1920–1940年代荷屬東印度與早期印尼建築風格,顏色透過礦物顏料滲入,不易褪色。當時流行的「花磚」通常由本地工坊依照歐洲設計生產,這種花紋常被運用在殖民時期的土生華人宅邸,或印歐混合風格建築 (Indo-European style) 的室內。

圖案外框最外層是一道深灰色實線邊框,接著是淺灰色背景上的黑色「希臘迴紋 (Greek key / meander pattern)」帶狀裝飾。這種希臘迴紋是殖民時期地板設計中常見的經典元素,象徵連續性與永恆。

內部區域中間是淺色底 + 深灰色斜方格 (diamond pattern),交點處有黃色四瓣花形裝飾。這種幾何+小花的搭配在當時既顯得歐式,又融入了一些本地審美 (花形可能受到爪哇或峇里圖案啟發)。

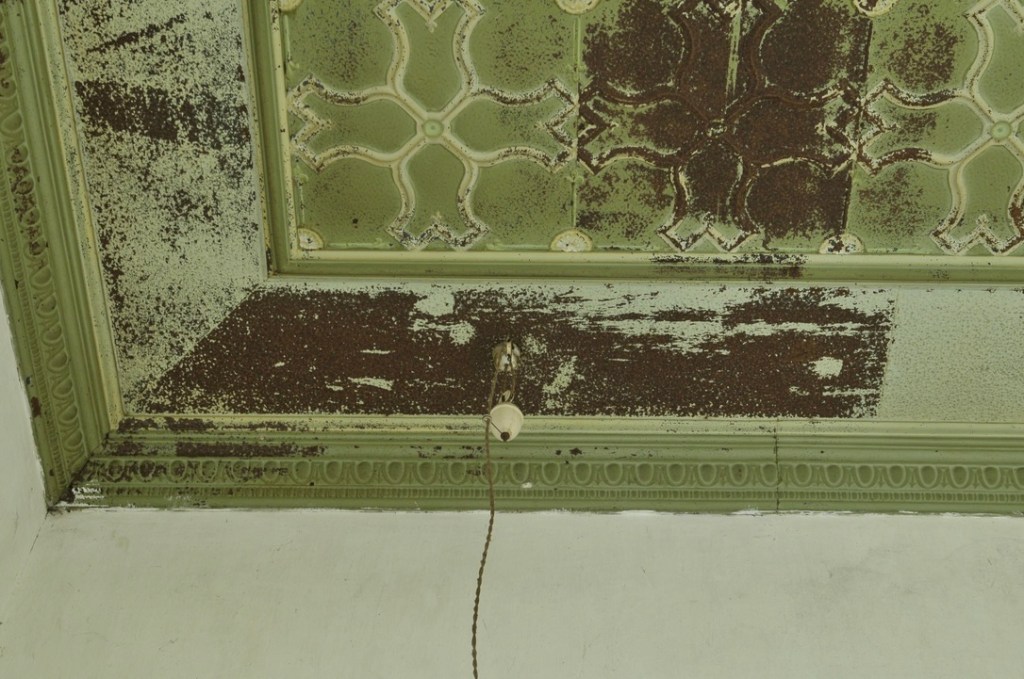

Ceiling Design

The ceiling is made using pressed metal (embossed tin), a technique that originated in Europe and North America, introduced to Asia in the late 19th century, and widely popular in colonial-era interiors until the mid-20th century. The central pattern is a continuous interlacing of geometric shapes, reminiscent of Moorish or Gothic window tracery, with small circular ornaments at each intersection. The edges are finished with decorative cornice moulding, featuring a continuous oval-chain pattern (egg-and-dart or bead motif).

In Indonesia, such ceilings were common between 1900 and 1940, especially in Chinese merchant houses and colonial buildings in cities such as Central Java, Surabaya, Semarang, and Bandung. The dark brown mottling and large patches of peeling likely result from paint oxidation and moisture damage, inevitable given the tropical climate and the passage of time.

Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

天花板設計

可以看見天花板屬於一種壓花金屬工藝天花板 (Pressed metal ceiling / Embossed tin ceiling),這種工法源自歐洲與北美,19 世紀末傳入亞洲,到 20 世紀中期以前,是殖民時期的主流風格,在許多亞洲國家也能觀察到。花紋樣式的中心是連續的幾何交織圖案 (類似摩爾式或哥德式窗格的交錯設計),每個交點有小圓點裝飾。邊緣有裝飾性檐口 (cornice moulding),採連續橢圓鏈狀 (egg-and-dart 或 bead pattern)。

在印尼,這種天花板盛行於 1900–1940 年間,尤其在中爪哇、泗水、三寶瓏、萬隆等城市的華人商宅與殖民建築。年代已久,加上氣候潮濕,黑褐色的大片斑駁應該是油漆氧化與潮濕造成的剝落與霉蝕。

Shifts in Material, Shifts in Identity

The living quarters of this family were formed by two or three interconnected buildings. The one we see now is particularly intriguing—its ground floor is almost entirely composed of Western classical elements, combined with wooden sunshades and a symmetrical doorway. In the middle, there is an access point leading up to the second floor.

Standing in the stairwell feels like pausing in a transitional space between body and mind. A slight tilt of the head reveals wooden and ironwork elements. Ascending further, the staircase is crafted from finer-quality wood, yet still adorned with Western-style decorative details. In other words, cement had simply been replaced by timber. A closer look at the handrail’s ornamentation and placement shows a striking compromise between Chinese-Indonesian and European styles.

材質的轉換與身份的移轉

這戶人家的生活範圍是由兩三棟建築體連結而成,目前所見的這棟建築這很有意思,一樓所見幾乎是西方古典元素,結合木料遮陽和對稱立門。中間一處可以上二樓。

佇立在樓梯間,恰好是身體和心境的一個過渡帶。輕輕抬起頭,便能看見木材與鐵件元素,再往上走,樓梯是用較好的木材打造,同時保有了西方元素的裝飾,換句話說,不外乎是將水泥換成了木料。仔細觀察樓梯手把的裝飾與安置,像極了一種印尼華人與歐洲風格的妥協與折衷。

The shift in material triggers our speculation: as one of the earlier waves of Chinese immigrants to arrive in Java, the family would naturally have built a house evoking memories of their homeland. For the Chinese, constructing a home in wood was often a symbol of wealth. Perhaps the owner’s taste had evolved, or perhaps his business had changed, making wood a more readily available resource.

Or was this upper floor an extension—a new façade designed to welcome Dutch officials?

Upon reaching the second floor, one can see that its internal structure incorporates both Eastern and Western elements.

面對材質的轉換使我們臆測:作為較早抵達爪哇島的一批印尼華人,自然會建造擁有家鄉印象的房屋。對華人而言,用木材打造房子顯然是一種財富象徵。或許是主人的品味有所改變,或許因為他的生意型態轉變,木材是更容易取得的資源。

或者,這棟樓是當時延伸出去的新門面,為了迎接荷官而設計的新空間?

走上二樓空間,可見到內部結構是採用東西方元素併用。

View of stairs and second floor | Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

Living Elsewhere, Heart in the Homeland

After years of traveling through Indonesia, I have observed that such mixed, interconnected buildings are most often found within Chinese family compounds. In today’s tide of Western modernization, cultural memory fades faster with each generation. Objects may still stir vivid and powerful emotions, yet for those living far from their ancestral land, the sentiment and sense of belonging—like the moon that shines brightest over one’s homeland—ultimately continue to follow the thread of Chinese history and heritage.

Whenever I encounter these fragments of time and history overseas, I am always filled with both gratitude and melancholy. After years of journeying, I’ve come to realize that the meaning of travel has shifted for me—it is no longer a reward for hard work, but a process of learning a way of life.

生活在他方,心中有故鄉

其實長年旅行印尼,會觀察到,這樣的混合連棟建築,大部分會發生在華人身份的家族。在今日西方現代化的洪流之中,文化記憶一代比一代流失的還快,物件雖然能勾起鮮明強烈的情感,然而生活在他方,月是故鄉明的情愫與認同感,終究還是會跟隨著華人歷史傳承下去。

當我在海外看見這樣的時間碎片歷史,心中總是既感激又感嘆的。經過行旅多年的體悟,對我而言,旅行意義也有所轉變,它並不是辛苦工作的犒賞,而是一種生活方式的學習過程。

View of another architecture with Chinese elements – Reception hall and gates | Photo credit: SUAVEART & J, private collector

Text by Yipei Lee

Special Thanks: Images courtesy of J, private collector from Indonesia.

撰文:李依佩

特別感謝:所有攝影照片來源 – J 朋友,私人藏家