Short Intro of CURATOR

Kodama Kanazawa (金澤 韻) is a contemporary art curator with extensive experience organizing numerous exhibitions both in Japan and abroad. After working for 12 years in public art museums, she began working independently in 2013. She obtained an MA in Curating Contemporary Art at Royal College of Art, the UK. Currently she is the Co-founder, Artistic director of Code-a-Machine (Kodama Kanazawa + Shinichiro Masui), and CIMAM member.

Curatorial Expertise & Interests

My curatorial work addresses issues of globalization and post-colonialism, including cultural imperialism in Japan’s modern and contemporary history, focusing on how societal and historical shifts alter human perceptions. I explore the psychological challenges these changes bring, seeking potential solutions through curating.

I collaborate with artists across a wide spectrum of mediums, from new media art and installations to painting and crafts. My curatorial approach is often experimental, aimed at finding more effective ways to communicate and engage with the artists’ work.

【From Coffee to Curating: A Day with a Curator】

After completing my graduate study, I began my curatorial career at a contemporary art museum. At the time, my boss was organizing one innovative exhibition after another. As I became familiar with the practices of the museum’s international advisors — such as Hou Hanru, Sarat Maharaj, and Bojana Pejic — I became captivated by the depth and complexity of curating. I came to understand that curating is much more than arranging artworks; it is a way of engaging with broader, layered discourses.

I believe exhibitions are powerful media for conveying important and nuanced ideas directly, without becoming overly didactic. I value them for their unique potential as interfaces that foster meaningful connections with audiences.

A museum curator’s role is to preserve artworks as part of humanity’s shared legacy for future generations — a deeply rewarding responsibility. At the same time, the position requires a high degree of specialization within a relatively narrow field. Much of a museum curator’s time is devoted to engaging with collections and archival materials related to art history.

However, I have always been drawn to art that exists between people, and to the exchanges that occur between people and artworks. This interest ultimately led me to pursue a career outside the museum.

While museum curators tend to focus on long-term institutional missions, independent curators respond more flexibly to timely and contemporary issues. Perhaps we could say that museum curators build the skeleton, while independent curators shape the soft, fluid spaces between the bones.

Though the work of independent curators may sometimes go unrecorded and fade from history, I feel that I am now curating around themes that genuinely inspire me, engaging directly with audiences, and experiencing a tangible connection to the world around me.

Yes, literature plays a significant role in my curatorial practice.

I’m sure that curators think through a scenario or narrative from the introduction to the conclusion of an exhibition. In my exhibitions, this scenario is sometimes presented explicitly as written texts. A good example is In Praise of Soils, an exhibition centered on the theme of soil, which took place in Shanghai. When the theme alone does not form a narrative, I intentionally construct one — often with a central character — to give audiences a focal point and guide their attention.

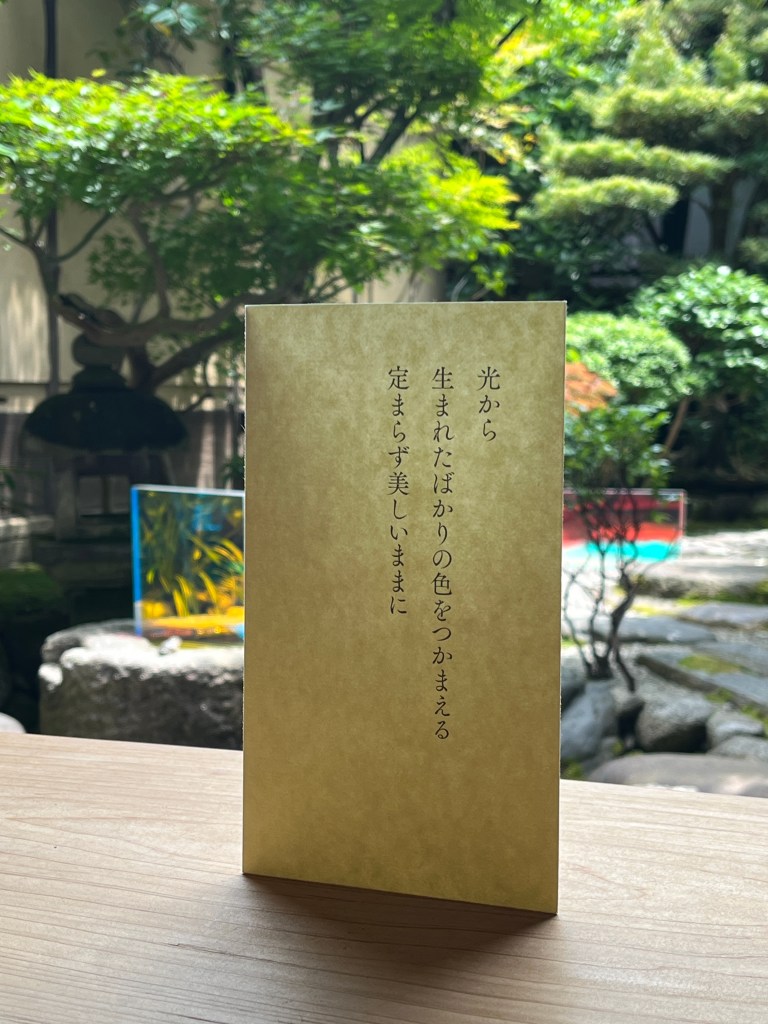

When I anticipate a diverse audience, I also incorporate poem-like texts to create a bridge between the artworks and the viewers.

At times, I commission professional writers or poets to craft these texts. However, when time or budget constraints arise — or when I want to avoid making the literary aspect too dominant, since it can be overwhelming for the audience when there are too many elements — I write them myself.

I find that words open up new channels of connection between artworks and audiences, activating underused parts of the imagination. It’s a fascinating and generative method that adds nuance and depth to the exhibition experience.

That’s true. I’ve also explored the realms of science and technology in several exhibitions, including projects with AKI INOMATA and Rafaël Rozendaal. My most recent exhibition was grounded in research on neurodiversity — a field that involves medical science and psychology. I believe that incorporating insights from other disciplines is essential to keeping art from becoming self-contained.

That said, I’ve never really paused to reflect on how I balance language, the human sciences, and the visual arts in my curatorial work. How do I do it…?

It’s difficult to articulate, especially in the moment. But perhaps I maintain that balance through a series of subtle adjustments — carefully choosing certain words, shifting the placement of a work ever so slightly. Maybe it’s through these small decisions that a sense of equilibrium is achieved.

I believe my mindset toward ecology and my vision for sustainability stem from being born and raised in an East Asian country. It’s rooted in a way of thinking — common in Japan, at least — that doesn’t draw strict boundaries between inside and outside, and that views nature not as something to be controlled, but as something to coexist with. In that sense, this perspective isn’t unique to me.

Still, if these sensibilities are strongly reflected in my curatorial work, it may be because I consciously resist treating the practices of artists working with ecological themes as events confined to the art world.

Instead, I’ve sought — through the languages of curation, such as words, color, and spatial composition — to place their work in dialogue with our present lives and the futures we hope to shape.

To add one more point, in 2019, the storage facility of the museum where I used to work was submerged due to a typhoon, and in 2022, I experienced a large-scale lockdown while living in Shanghai. These events gave me an opportunity to deeply reflect on both natural and social disasters.

Since 2011, I also feel that the Great East Japan Earthquake and the nuclear power plant accident have remained as a kind of underlying resonance. Although these experiences rarely become the central theme of my exhibitions — Gazing at Spring being a special exception — they have certainly altered my worldview and outlook on life, which may in turn influence the way I curate.

Ultimately, when asked what curators can do in the face of the environmental crisis, I believe the answer lies in learning about the practices of artists who respond to this issue with sensitivity — and in finding more effective ways to present and share their work with the world.

When I first moved to China, I wondered how people managed without Facebook or Google. But I quickly discovered that equivalent platforms were fully developed, and life carried on smoothly. It felt as if I had arrived in a world built on the far side of the moon — though from their perspective, perhaps it’s the world with Facebook and Google that’s on the far side.

I believe it’s valuable to have more experiences that flip your perspective. Every time your worldview is turned upside down, you become more relativized, more flexible, and more open to absorbing new ideas.

Whenever I work with artists from around the world or curate exhibitions outside my home country, I feel these cross-border experiences strengthen me. There is always a tension between locality and globality, and the challenges of cultural translation range from minor nuances to deeply complex issues. Still, I believe that as long as we remain flexible, most obstacles can be overcome — especially through close collaboration with local teams.

I don’t necessarily view the stimulation of the sensorial experiences or the creation of spectacle in a negative light. However, I cannot emphasize enough that the legitimacy and strength of an exhibition’s concept are far more important in curating.

I believe that once a concept is firmly established, sensory stimulation and spectacle naturally take their place as secondary, supporting elements.

I’m genuinely glad to hear that you see a strong research orientation in my work—but I must admit, I have somewhat mixed feelings about this topic. May I share them?

In the past, as a graduate student, I was deeply immersed in academia. Later, as a museum curator, I conducted research and shared some of those findings through exhibitions. However, museum work was often demanding, and I couldn’t always pursue research as deeply as I had hoped.

Since becoming independent, my research activities have been truly minimal — limited to the bare essentials. When I speak of “research,” I mean the comprehensive study of primary sources or materials close to them, gaining new insights, and situating those within broader bodies of knowledge. Such inquiry is incredibly difficult to sustain outside of institutions like museums or universities.

So, while I continue to value research deeply, I also feel a sense of distance from it—and that’s what gives rise to the mixed feelings I mentioned.

That said, I don’t believe I’ve been entirely disconnected from the development of knowledge since becoming independent. Through collaboration with artists, I interpret the meanings that emerge from our lived experiences — through color, form, texture, and the nuances of each practice. I weave these elements together to create a cohesive experience that takes shape as an exhibition.

As audiences move through the space, they encounter and absorb something new with each step. It’s a form of knowledge acquisition — distinct from reading a scientific paper, but no less meaningful.

When organizing an exhibition, I often remind myself, “I’m not a university researcher.” Academic papers convey an overwhelming amount of information, but they aren’t always easily digestible for a broader audience.

What I aim to do is something different: I try to create conditions where the raw insights gained by the artists can be sensed and grasped by the audience, almost directly..

I spend a lot of time discussing with artists about what they are doing, what they hope to do, and what visions I have in mind. Together, we decide on the atmosphere of the space. The thematic focus of the exhibition and the architectural character of the venue are also important factors in this process.

Sometimes the result is minimal and stripped-down, like vegetables simply grilled and seasoned with salt. Other times, it may push forward with a single bold tone, like a bowl of Ramen. Or, it can unfold like a carefully orchestrated French course: a succession of complex, nuanced flavors delivered with precision.

The language of curation encompasses not just color, form, and text. It also involves light of varying intensity and quality, the visual texture of materials, scale, spatial distances, air flow, temperature, and even the historical context of the exhibition site. Naturally, different curators have varying strengths when working with these elements. As for me, I find this process quite enjoyable.

I appreciate you describing my work in such a wonderful way — it truly means a lot. I wish I could say, “Yes, that’s exactly the intentional strategy behind my curating,” but in truth, it’s not always calculated to that extent.

What I do try hard to do, though, is to ensure that the themes I work with are valid and meaningful for those of us living through this time together. I aim to present them in a way that neither imposes nor withdraws too much — just enough for the audience to receive the message openly.

I believe that within every human being resides both profound despair and a powerful sense of joy. We may face serious illness, discrimination, or the loss of someone dear — life in this world is undeniably hard. It’s painful even to think that we will eventually part ways with everyone we love.

And yet, perhaps because of that, I find myself deeply moved by how warm and full of happiness the world around us can be. In the end, I feel that I create exhibitions with artists to gently bring people — if only for a moment — back to this deeper truth of our world..

When I was studying curating in graduate school, my professor told me to see at least 20 exhibitions a week. I have to admit, I haven’t managed to keep up that pace myself, but even so, I still recommend seeing as many exhibitions as you can, and revisiting the ones that intrigue you. And like Susan Sontag, I also recommend traveling — or if that’s not possible, then reading, to embark on journeys of the mind. In short, I encourage everyone to find ways to keep themselves in a fresh state. I promise, I will try to do the same.

【Additional exhibition photos】

Interviewer: Jin-man Pei

Editor: Yipei Lee

Special thanks: Kanazawa Kodama

Photo credit: AKI INOMATA, Maho Kubota Gallery, Oka Haruka, Shinichiro Masui, Aurélien Mole, Oyamada Kuniya, O LamLam

From Coffee to Curating: A Day with a Curator is a series of dialogues with curators who are deeply engaged in the art of curation, knowledge exchange, and cultural storytelling. Through this column, we’re pulling curators out from behind the scenes and into the spotlight. In these fun, candid interviews, we invite you into their world—from early morning coffee rituals to late-night brainstorming sessions. Discover the sparks of inspiration, unexpected creative turns, and everyday hustle that shape the exhibitions we see and feel. It’s about the people behind the practice, and the passions that keep them going.